Adrian Tchaikovsky: How I Write

The author of the Echoes of the Fall trilogy and the Arthur C. Clarke Award-winning Children of Time shares an insight into his writing process.

Adrian Tchaikovsky is the author of many science fiction and fantasy books including the Echoes of the Fall trilogy, the Arthur C. Clarke Award-winning Children of Time and The Doors of Eden. We asked him how he writes his books, and here he gives us an insight into his writing process.

Looking for more science fiction? Discover our edit of the best sci-fi books.

Looking for more fantasy? Don't miss the best fantasy books of 2020.

“Backwards” is probably not the most constructive thing to say, in answer to that question. “Doing it wrong” is also, I suspect, another popular interpretation.

Every writer has their own method, of course, and everyone’s “right” and “wrong” are going to be different, but I have a stuffy voice in the back of my head talking about starting with plot and character and keeping everything else pared down to a minimum, and of course is there anything quite as gauche as worldbuilding in all the respectable writing manuals? And I’m probably manufacturing that voice out of whole cloth and some terrible creative writing article from thirty years ago, but something still sits on my shoulder telling me, “You know, proper writers don’t do this sort of Dungeons and Dragons nonsense . . . ”

So: I start with the setting, the world. That’s what fires me up about writing a fantasy or SF book. I honestly don’t think I could do it any other way. “I want to write a story about a middle-aged politician pulling the tail of a merciless empire and doing spy stuff” is not going to germinate into Shadows of the Apt. “A girl is torn between her mother and her father’s heritage and runs away to find herself” isn’t going to give you the shapeshifters of Echoes of the Fall. But “A world where everyone has the powers of insects and some of them can do steampunk and others can do magic” gives you Stenwold Maker and his spy rings and clashes with the Wasp Empire. “A world where everyone is a shape-changer” leads very naturally to Maniye springing Hesprec from captivity and running off into the woods.

For me, it’s getting the world in place, in detail, consistent and immersive to me, that gives me my characters and plots. Stenwold and Cheerwell, Tisamon and Grief in Chains, they all arise from the world itself. The clashes between Collegium and the Empire, the tragedy of the Mantis-kinden, the technological acceleration of the Air War, all these are the driving plots of Shadows of the Apt, but they also follow organically from the setting, and from each other. At the end of Salute the Dark, I could just stand back like a farmer after planting, and see exactly what would grow from that combination of world details and past events.

Everything in Children of Time arises out of my desire to explore the world of the Portiids. Even major details like Understandings arise as emergent properties of the settings, and then get put to work like little scuttling pit ponies for the benefit of my imagination. Get the world right and the story will emerge, and it won’t just by “go everywhere on the map and then defeat the dark lord” unless the world you have made is as flat and dreary as that. In making a detailed world you create complexity – multiple viewpoints, philosophies, cultures, a riot of diversity, and just like in real life the interaction of those complex systems go on to create things you wouldn’t necessarily have ever thought of alone.

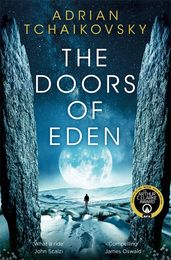

The Doors of Eden

by Adrian Tchaikovsky

When Lee and Mal went looking for monsters on Bodmin Moor, only Lee returned. She thought she'd lost Mal forever, but now she's back. What happened that day? And where has she been for the past four years? Lee isn't the only one with questions, MI5 are also very interested in Mal's return.

Meanwhile, Julian Sabreur's investigation into an attack on physicist Kay Amal Khan has lead to a clash with powerful agents who may not even be human . . .