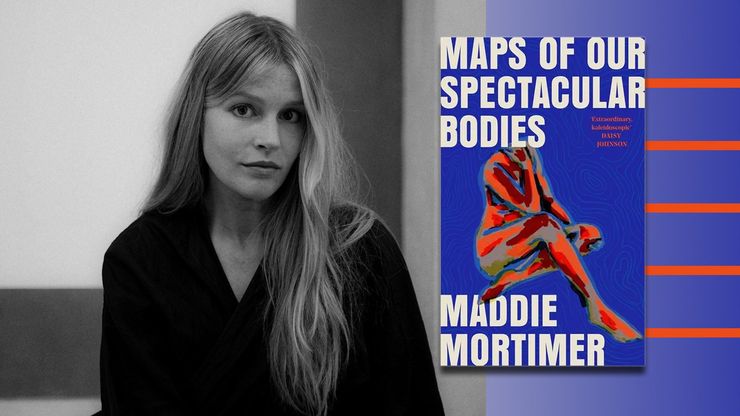

Maddie Mortimer on the rise of the genre-bending book

Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies is the incredible genre-defying debut novel from Picador super-lead Maddie Mortimer. Here, she discusses the place of the novel in literature and her favorite genre-bending novels that are pushing the form.

When I was eighteen, I noticed a Colm Tóibín quote on the back of a book that struck me as odd. The book was Anne Carson’s Decreation, a dazzling collection of poetry, essay and opera. The quote read: 'If she was a prose writer, she would be instantly recognised as a genius’. It stayed with me. I couldn’t understand why ‘prose’ (or, by extension, ‘the novel’) sat firmly at the top of the great invisible literary hierarchy. Even today, I believe I turned to prose because I wasn’t a good enough poet. I loved stories from a young age, I loved reading and writing them, but what made my brain fizz and my heart soar most was metaphor — the rhythm and the sound of a sentence, the little hidden melodies.

I have always been a restless reader. My eyes will dart around the surface of a page before settling and sinking anywhere; I am distracted by the shapes of words, or the way a paragraph floats. This isn’t, perhaps, surprising, considering how short our attention spans are today, and the fact that we receive information in fragments, short sound bites, summarised quotes and flickering images. It is a remarkable and sacred thing that for all the technological advances, many novels being published today look exactly like those being published in 1850. But then, of course, there are exceptions; unconventional, hybrid books that find very new ways to tell familiar tales, and these have always excited me.

‘What made my brain fizz and my heart soar most was metaphor — the rhythm and the sound of a sentence, the little hidden melodies. ’

Whilst Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies is, at its heart, a family drama — it is also a formally ambitious novel. There are three narrative threads in the book that are not only in constant communication, but are actively competing against one another to ‘tell’ the story. The events happening in Lia’s past and present are mapped onto the landscape of her body, the first person eats away at the third, there are fragments of anatomical science and religious philosophy, of poetry, painting and dance and typographic moments where words drip, or swell, as if magnified — they mirror and bend. By experimenting with form like this, by shifting between styles and building up patterns to pick at and unravel I found that the novel had become about the very act of storytelling; about the way we choose to frame our lives, and which version of ourselves we let take the lead. As Lia (an illustrator with a vast imagination) nears death, she is attempting to make sense of her choices, her illness. The piecing together of self is her final creative act.

I started writing the book when I was 23, and for all the play and ‘fizz’ there were also simple delights that emerged unexpectedly along the way. I learnt that a fully realised character or frank, honest dialogue can be just as poetic as a perfectly constructed metaphor, or a bit of clever word play. This, I think, is growing up. It’s realising that you have nothing to prove. It’s leaving your coat and scarf and pretension in the hall, taking the hands of your characters, and letting them lead you through the house.

Here are some contemporary novels that have made a book like Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies possible. I consider all of them works of genius — not because of their prose or their poetry, their profound intelligence or impressive architecture, but because of the sheer confidence with which they go about being exactly what they are, and by doing so - defy category.

Autobiography of Red

by Anne Carson

'Words, if you let them, will do what they want to do and what they have to do.'

This novel in verse is a loose retelling of the Myth of Geryon and the tenth Labor of Heracles. It’s also a queer coming of age story that captures the profound agony and bizarre beauty of loneliness, monstrosity, desire and artistic expression like no other. Full of neologisms and the most sublime words in the most surprising order. Carson leads the way.

Lincoln in the Bardo

by George Saunders

This Booker prize-winning masterpiece has 166 narrators. Most of them are dead. Together, they account the events that take place after president Lincoln’s son Willie’s death. I return often to the bardo to be reminded of ambitious form that never looses sense of itself; that serves the narrative rather than swamps it.

The Familiar, Volume 1: One Rainy Day in May

by Mark Z Danielewski

Very early on in the writing process, someone pointed me in Danielewski’s direction. ‘A House of Leaves’ was his postmodern masterpiece that achieved cult status, but there are some thrilling moments in ‘The Familiar’ (Vol 1) too – a novel in which a 12-year-old epileptic girl finds a kitten and loads of other seemingly unrelated things happen in different countries and timelines. Shapes tumble into the spine. There are so many fonts. Like me, you might not understand or be able to follow it all, but it’s worth dipping into from time to time just to remind you of what a physical thing a book can be. It inspired me to make Maps as much of a visual experience as possible.

Grief is the Thing With Feathers

by Max Porter

Most people have heard of this book by now, and that’s a wondrous thing considering it’s a small hybrid gift of a thing that reads like poetry, features a talking crow and a widowed Ted Hughes scholar. I love it for it’s sheer gut-punch fun and it’s linguistic playfulness, but mostly for it’s way of reducing me to tears at any given moment. It was the spark that lit the fire, really.

Multiple Choice

by Alejandro Zambra

Thin, simple, and oh so clever, this is an interesting example of a book where the form is indivisible from the subject matter. Made up only of multiple choice questions, it borrows its structure from the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test and interrogates the educational system under Pinochet’s dictatorship. Turning participation into poetry, Zambra manages to guide us through issues of censorship, choice, ignorance and accountability without it ever feeling heavy handed.

The White Book

by Han King

King’s meditation on colour and grief is a treasure box of objects you want to keep on turning over and over. Contained to one brief, centred paragraph per page, the writing is eerily clean, peaceful and mysterious. She speaks to the still part of the mind.

Checkout 19

by Claire-Louise Bennet

Unlike the others, this novel isn’t fragmentary but appears in thick walls of text throughout. Reminiscent of Renata Adler, another author that I love, Bennet’s prose is wickedly funny and breathless and exhausting but written with the upmost control. At once Checkout 19 feels like a piece of literary criticism, then a coming of age novel, then a dissection of the human imagination and then none of those things. Richly allusive and eclectic in all the best ways I think Claire Louise Bennett is one of the best stylists writing today.

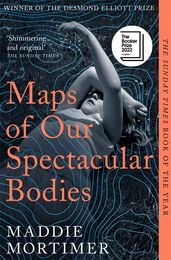

Discover Maddie's own shimmering debut novel, releasing with Picador on 31 March:

Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies

by Maddie Mortimer

Something is on the move in Lia's body: something shape-shifting, gleeful and malevolent. And it's spreading... When a sudden diagnosis changes Lia's world, the gap between her past and her present starts to crumble. Secrets awake within her, and the outer landscape blends with that within. And Lia and her family must face the most difficult of questions: how do you die with style, when you're just not ready to go?