Survival of the grossest: femgore's final girls

Messy, rageful, excessive and often downright disgusting, horror's new heroines are taking a knife to the genre's archetypes.

Femgore, the latest visceral subgenre of horror fiction, is becoming as hard to escape as its vengeful, grotesque and occasionally flesh-eating female protagonists and the everyday brutality of womanhood they're responding to. Centring female characters and experiences, and challenging clichés of femininity, femgore not only takes aim at the patriarchy but explores women's relationships with themselves, their bodies, their emotions and with other women. Here, author, historian and content creator Jean Menzies, a voracious reader of the subgenre, explores how the women of femgore compare to the traditional heroines of horror.

Horror’s heroine: the final girl. She is brave, beautiful, and strong. She is young, toned, and somehow her legs are always hairless even while stranded in the wilderness. She is that emblem of the male gaze, the virginal sex symbol. Now, don’t get me wrong. The final girl can subvert her own existence. I love Sydney Prescott (Scream, 1996) as much as the next horror fan. She is a legend and rightly so. Yet there is an issue with final girl supremacy more widely that has always tickled at my brain. She is the archetypical it-girl of horror. She is the definition of survivor. In many ways, however, she is also another unrealistic standard for women to judge themselves against. It's not enough to simply survive. You must also be virtuous and likeable and righteous. In other words: perfect.

What about the women who aren’t perfect though? Perfect victims. Perfect survivors. Perfect anything. The messy women. The complex women. The real women. What about them? Enter femgore, the latest subgenre in horror cinema and literature. In essence the term refers to stories that centre women and, surprise, surprise, throw in a little gore. But beneath the surface this growing genre is so much more. Femgore is antithetical to everything women in horror have been told they have to be. The femgore heroine is messy, rageful, emotional, excessive, over the top, and even downright disgusting. She is fully herself. Her rage doesn’t have to be righteous, and her skin doesn’t have to be flawless. She blurs the lines between survivor and perpetrator, complicating the question of what constitutes survival.

‘Her rage doesn’t have to be righteous, and her skin doesn’t have to be flawless. She blurs the lines between survivor and perpetrator, complicating the question of what constitutes survival.’

I’m always reticent to suggest that a subgenre is truly new. There have, of course, always been women in fiction and horror that defy the expectations of their genre. There have always been those who subvert the tropes that fight to define womanhood. Yet, the recent rise in the popularity of femgore is undeniable. From Mona Awad’s novel Bunny (2019) where a college clique transforms bunnies into men, to Coralie Fargeat’s film The Substance (2024) where an aging celebrity experiments with a drug that unleashes a younger version of herself. From Rory Power’s novel Wilder Girls (2019) where teenagers are quarantined while awaiting a cure for a toxin that transforms their bodies, to Ashley Lyle and Bart Nickerson’s show Yellowjackets (2021 -) where a girls soccer team are forced to eat or be eaten in the Canadian wilderness. Femgore doesn’t shy away from the gory details.

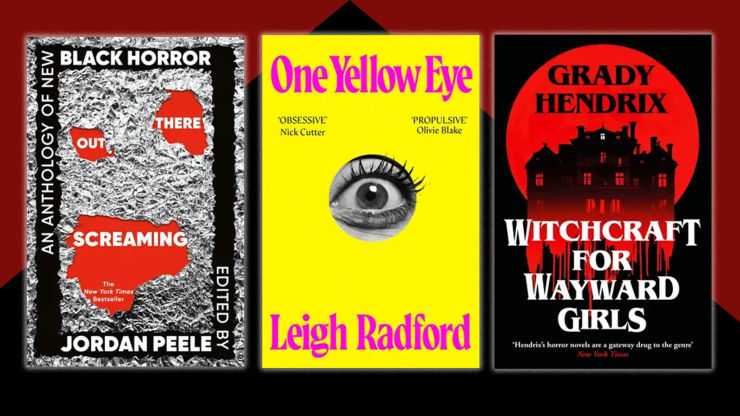

And there is still more to come. In One Yellow Eye by Leigh Radford, protagonist Kesta is scrambling to survive something far worse than the recently quashed zombie apocalypse – something intangible that gnaws at her inside. Meanwhile, the protagonists of Olivie Blake’s Girl Dinner are fighting to not just survive an academic world riddled with misogyny but a deliciously bloody new wellness trend. . . The very concept of survival takes on new meaning in these complex tales of grief, ambition, and womanhood.

The gore is there. In the fleshy feasts and terrifying transformations. Yet, the horror is not in the gore, not really. It’s in the recognisable. The pressure to conform, the body dysmorphia, the diet culture. It’s in the pressure to appear put together, to recover as quickly and quietly as possible. What femgore does is give these very real issues a tangible quality. The devastation of our hearts and minds bleeds onto the page (and screen) so that everyone can see it, in all its grotesque and unsettling glory.

‘The gore is there. In the fleshy feasts and terrifying transformations. Yet, the horror is not in the gore, not really. It’s in the recognisable. The pressure to conform, the body dysmorphia, the diet culture. It’s in the pressure to appear put together, to recover as quickly and quietly as possible.’

In fiction past and present violence against women has been a prop. Women stuffed into fridges so that their partner or a jaded local detective might experience some sort of personal growth (see Dead Girls by Alice Bolin, 2019). They are expendable bodies who do not exist beyond their relationship to the hero. Femgore on the other hand rejects the way in which popular horror and media in general has managed to simultaneously infantilise and sexualise women. How it has whittled us down to one-dimensional caricatures and then been aghast when we don’t live up to these expectations in real life. Femgore is a form of horror where women are set free – free to feel – free to fail – free to be. The femgore protagonist is not our role model or a man’s feminine ideal. She just is. There is no moral judgement, one way or another. Instead, we as readers are simply presented with it all: the slimy, sticky, sullied complexity of existence.

Survival, femgore reminds us, isn’t always glamorous. Still, monstrous and messy, it is survival, nonetheless.