The most misunderstood characters in literature

‘Monsters’, mysteries and figures of fear. Here are five characters we think deserve a second chance.

Literature is littered with the mistreated, the misjudged and the unfairly maligned, figures misunderstood by both their fellow characters and readers alike. Here, we present five literary or mythical characters for your reconsideration.

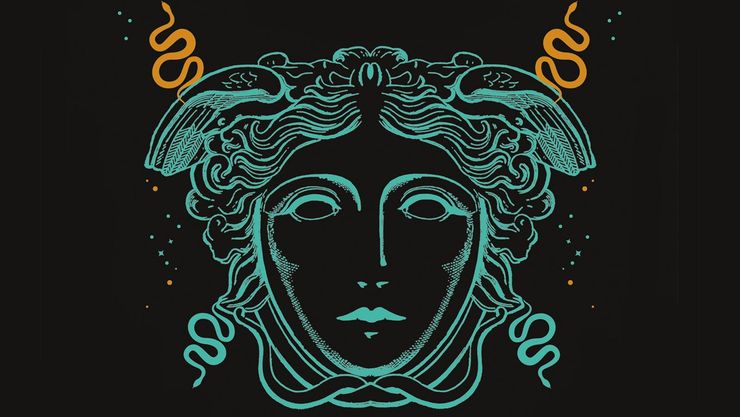

Medusa

Stone Blind

by Natalie Haynes

What do you see when you think of Medusa? Snakes, probably. People turned to stone. Perseus the hero holding her severed head aloft. The perception of Medusa and her sisters as spiteful, horrifying creatures is so entrenched that their collective name, gorgon, is now a dictionary-official insult: ‘a fierce, frightening, or repulsive woman’.

What if Medusa wasn’t just a monster waiting to be slain, but had a life, conversations, relationships? What if she had more than just a bit part in someone else’s origin story? Enter Stone Blind. With her acerbic wit and trademark feminism, Natalie Haynes makes Medusa as much a part of the legend of Perseus as Perseus himself. And by hearing her full story, we can properly appreciate just how terrible it is. Medusa is not a monster, she is treated monstrously. Haynes’ novel can’t change that, but it finally makes us see it.

Mildred Bevel

Trust

by Hernan Diaz

Who is the real Mildred Bevel? We first meet her as Helen Rask, the character based on her in Harold Vanner’s transparent novelisation of her husband, Andrew Bevel’s, life. But perhaps she is really the ‘too fragile, too good for this world’, purveyor of ‘domestic delights’ described in the memoir Andrew begins in order to set the record straight. Or is the reality closer to the shadowy, enigmatic subject of his memoirist, Ida Partenza’s, investigations?

Trust tackles the idea of stories being taken and changed by others head on. An examination of truth, fiction, money and the manipulation of all three, Trust’s four narratives, although presented consecutively, are in constant conversation, increasing our understanding of Mildred as they knock it askew. Can we ever fully understand someone until we hear directly from them?

Frankenstein’s Monster

Frankenstein

by Mary Shelley

The incredible influence of Mary Shelley’s novel means that it’s easy to get the wrong impression of Dr Frankenstein’s creation without even reading the book. We feel like we already know him, and it can be hard to separate the creature thought up in 1818 from the green-skinned, neck-bolted depictions of popular culture. To make things worse – with a nod to fellow literary pedants everywhere – a lot of the time we can’t even get his name right (Frankenstein is the man who created the monster).

Within the book itself, he is cruelly misjudged by both his creator, Dr Frankenstein, and, initially, the reader. Introduced to us through the perspectives of others, the Creature appears as a hideous, murderous monster. But when allowed to speak, he shows himself to have begun life as a gentle, fearful figure, who has learned to hate humans only through being so badly treated by them.

Bertha Rochester

Jane Eyre

by Charlotte Brontë

We’re aware of Bertha’s presence in Charlotte Brontë’s classic novel long before we actually meet her. The strange laugh Jane hears; the mysterious attacks in the night. Locked in the attic for more than a decade, Edward Rochester’s ‘mad’ first wife is dehumanised by both language (‘it’, ‘savage’) and her role in the plot, a horrifying Gothic obstacle in our heroine’s path to marriage.

Depending on when (both in terms of your own age, and the age you’re reading in) you first come across Jane Eyre, it can take a re–read or two before you start to consider things from Bertha’s point of view, and it took a hundred years for her to be given a voice. Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, written in 1966, offers readers Bertha’s life story and perspective, and an understanding of how and why she came to be the ‘mad woman in the attic’, finally releasing her from that image.

Arthur ‘Boo’ Radley

To Kill a Mockingbird

by Harper Lee

The unseen, unheard neighbour of the Finch family, Boo Radley is the subject of rumour, fascination and fear amongst the children of Maycomb. His physical absence, and the adults’ refusal to talk about him, turn his shyness and desire for solitude into something sinister and threatening. Yet on the few occasions he, or the results of his actions, actually appear in the novel, he demonstrates affection for the Finch children and a desire to protect them.

Harper Lee’s writing cleverly lets us see him from nine-year-old narrator Scout’s perspective whilst also allowing us an older reader’s understanding and empathy for his situation – something Scout develops herself at the end of the novel.