Black and British: David Olusoga uncovers a forgotten history

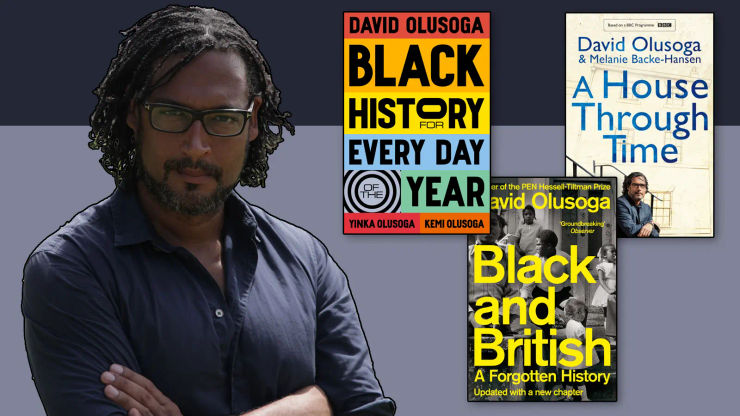

Here, historian and broadcaster David Olusoga discusses the inspiration behind his book Black and British: A Forgotten History, and shares just some of the books he feels are most important on the subject of black British history.

David Olusoga introduces his book Black and British: A Forgotten History, a revealing exploration of the extraordinarily long relationship between the British Isles and the people of Africa which accompanied his landmark BBC series, and pays tribute to the pioneering works on black British history that inspired it.

I stumbled upon the subject that was to become my vocation out of a simple love of story, and because of a gung-ho fascination with the Second World War that was almost obligatory among boys of that period, whatever their racial background. Britain of the 1980s was a nation still saturated in the culture and paraphernalia of that conflict. For the white working-class community that I grew up in, the war was the most exciting and significant event ever to collide with our terraced streets and decaying factories. It had changed the lives of my white grandparents, whom I loved deeply, and I was intoxicated by the thought that German bombers had prowled the skies above my home town and that my grandfather had scanned those skies while on watch on the roof of the Vickers Armstrong factory by the River Tyne, where he worked building tanks.

I wandered into history looking for excitement. I never expected that there I would encounter black and brown people who were like me and my family.

I was alerted to those stories of presence and participation by my white mother, and I stumbled across more and more stories of black British people as my interests took me further back, into the nineteenth and then the eighteenth century.

In 1986 I came across the book Staying Power by the British journalist Peter Fryer. It was, I believe, the first book I ever bought for myself with my own money. This history of the black presence in Britain was published in 1984, the year in which my family had been besieged in our home, and it set the racism that had so deeply affected our lives within a historical context. It allowed me to understand my own experiences as part of a longer story and to appreciate that in an age when black men were dying on the floors of police cells, my own encounters with British racism had been relatively mild. For me and for thousands of black and white people who read Fryer's book its effect was transformative. Fryer took his readers back through the centuries and introduced us to an enormous pantheon of black historical characters, about whom we had previously known nothing.

Those black Britons have been with me ever since. I have visited their graves and read their letters and memoirs. They have become part of British history and in some cases part of the national curriculum. Staying Power remains a uniquely important book and anyone who has ever written about black history has found themselves referencing it, quoting from it or seeking out some of the myriads of primary sources it drew together.

Fryer's eloquent chapters offer guidance and provide orientation through a complex and fractured history. Although not the first work of black British history its impact spread further than most, in part because its publication came at a crucial moment, three years after a wave of riots sparked by hostile policing set ablaze black neighbourhoods of London, Bristol and Liverpool.

Staying Power was part of a wider process of historical salvage. It was one of a number of pioneering books of black British history that recovered lost people, reclaimed lost events and reassessed the significance of racism in British history. Just as important were Black and White by James Walvin (1973) and Black People in Britain by Folarin Shyllon (1977).

The books that came out of that wave of new research were in part an attempt to compensate for the failures and myopia of so-called mainstream history. When Fryer, Walvin and others were writing it was not unusual for books on the British eighteenth century to make no mention of slavery and the slave trade or concentrate only on the abolition of those institutions.

The presence and role of black people in the British story were all too often ignored completely or else reduced to footnotes. When black figures did appear they were often mute and passive, the victims of slavery or the beneficiaries of abolition.

Black history was so poorly understood at that time that when James Walvin embarked upon his research he wrote to every county archivist in Britain asking them if they had come across any forgotten black figures in the documents they cared for. What this first wave of black history writing demonstrated was that while post-war migration had been unprecedented in scale it had not marked the beginnings of black British history. Thanks to their work it is today well understood that people of African descent have been present in Britain since the third century, and there have been black ‘communities' of sorts since the 1500s.

This book and the BBC television series it accompanies are a modest attempt to build on the work of those earlier historians and to bring the histories they uncovered to new audiences. But it is also a tentative endeavour to reimagine what we mean by ‘black history' and ask where its borders might be drawn. The black history of Britain is by its nature a global history. Yet too often it is seen as being only the history of migration, settlement and community formation in Britain itself.

Black British history is as global as the empire. Like Britain's triangular slave trade it is a triangular history, firmly planted in Britain, Africa and the Americas. On all three continents stand its ruins and relics. Black British history can be read in the crumbling stones of the forty slave fortresses that are peppered along the coast of West Africa and in the old plantations and former slave markets of the lost British empire of North America. Its imprint can be read in stately homes, street names, statues and memorials across Britain and is intertwined with the cultural and economic histories of the nation.

This book is an experiment. It is an attempt to see what new stories and approaches emerge if black British history is envisaged as global history and – perhaps more controversially – as a history of more than just the black experience itself.

Like anyone writing on black British history, I am indebted to the works, observations, research and insights of others before me. If this book has anything in common with the pioneering works of Fryer, Walvin and others it is that it is written in the firm belief that Britain is a nation capable of confronting all aspects of its past and becoming a better nation for doing so.

Black and British: A Forgotten History

by David Olusoga

Black and British: A Forgotten History is an important re-examination of a shared history and the revealing story of the long and complex relationship between Britain and the people of Africa and the Caribbean.

Listen to an audio extract from Black and British: A Forgotten History

Explore the best history books to enrich your understanding of the past.