The 50 best history books of all time

Spanning both centuries and continents, discover our edit of the best non-fiction history books.

As the oft-repeated quote by George Santayana goes, ‘Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ The past fascinates historians and readers alike, and history has much to teach us about our present and future. Here’s our edit of the best history books of all time.

Looking for fiction? Discover our edit of the best historical fiction books of all time.

The best books on ancient & early history

Tutankhamun's Trumpet

by Toby Wilkinson

It is over one hundred years since Howard Carter first peered into the newly opened tomb of ancient Egyptian boy-king, Tutankhamun. When asked if he could see anything, he replied: ‘Yes, yes, wonderful things.’ In Tutankhamun’s Trumpet, acclaimed Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson takes the objects buried with the king as the source material for a wide-ranging, detailed portrait of ancient Egypt – its geography, history, culture and legacy. One hundred artefacts from the tomb, arranged in ten thematic groups, are allowed to speak again – not only for themselves, but as witnesses of the civilization that created them.

A (Very) Short History of Life On Earth

This lyrical and moving account takes us back to the early history of the earth – a wildly inhospitable place with swirling seas, constant volcanic eruptions and an unstable atmosphere. The triumph of life as it emerges, survives and evolves in this hostile setting is Henry Gee's riveting subject: he traces the story of life on earth from its turbulent beginnings to the emergence of early hominids and the miracle of the first creatures to fly. You'll never look at our planet in the same way again.

The Greatest Invention

by Silvia Ferrara

This book tells the story of our greatest invention – the invention of writing. Writing allowed humans to create a record of their lives and persist past the limits of their lifetimes. The Greatest Invention explores the origins of our very first scripts in China, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Central America, deciphering the ancient stories and teasing out the timeless truths of human nature in our desire to connect, create and be remembered.

Pandora’s Jar

by Natalie Haynes

The Greek myths are among the world's most important cultural building blocks and they have been retold many times, but rarely do they focus on the remarkable women at the heart of these ancient stories. Now, in Pandora's Jar: Women in the Greek Myths, Natalie Haynes – broadcaster, writer and passionate classicist – redresses this imbalance. Taking Pandora and her jar (the box came later) as the starting point, she puts the women of the Greek myths on equal footing with the menfolk. After millennia of stories telling of gods and men, be they Zeus or Agamemnon, Paris or Odysseus, Oedipus or Jason, the voices that sing from these pages are those of Hera, Athena and Artemis, and of Clytemnestra, Jocasta, Eurydice and Penelope.

Divine Might

by Natalie Haynes

In Divine Might Natalie Haynes, author of the bestselling Pandora’s Jar, returns to the world of Greek myth and this time she examines the role of the goddesses. We meet Athene, Artemis, Aphrodite and Hera; each with their own story. We also meet Demeter, goddess of agriculture and mother of the kidnapped Persephone, we sing the immortal song of the Muses and we warm ourselves with Hestia, goddess of the hearth and sacrificial fire. These goddesses are as mighty, revered and destructive as their male counterparts. Isn’t it time we looked beyond the columns of a ruined temple to the awesome power within?

A World Beneath the Sands

by Toby Wilkinson

The golden age of Egyptology was undoubtedly the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a time of scholarship and adventure which began with Champollion's decipherment of hieroglyphics in 1822 and ended with the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon a hundred years later. In A World Beneath the Sands, the acclaimed Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson tells the riveting stories of the men and women whose obsession with Egypt's ancient civilisation drove them to uncover its secrets.

The best books on British history

Eleanor

by Alice Loxton

Explore the legacy of Eleanor of Castile, the beloved wife of King Edward I. Bestselling historian Alice Loxton goes on an epic 200-mile pilgrimage from Lincoln to London, walking the exact route of the solemn funeral procession held for Eleanor when she died in 1290. To mark the places where her cortege rested, a heartbroken Edward commissioned twelve magnificent Eleanor Crosses, which still remain on the route. As Alice journeys in search of England’s forgotten Queen, over ancient paths and modern motorways, history comes alive in surprising ways. Lively and entertaining, Eleanor uncovers the extraordinary life and formidable character of this lesser-known royal.

The Discovery of Britain

by Graham Robb

Taking you on a time-travelling adventure around the 'spindly, sea-wracked islands' we call home, The Discovery of Britain is history that's panoramic and intimate, poignant and shocking, seriously funny, and enlightening in the most surprising way. We encounter an entertaining cast of characters foreign and homegrown, drop in on places and events, and dwell on the successes and catastrophes across British history. From ancient settlements swallowed up by the sea and the creation of Stonehenge to the advent of multiculturalism and recent political earthquakes, all is seen as it’s never been seen before.

Eighteen

by Alice Loxton

How do you make a living in Georgian London with no arms or legs? What would you do if a world war interrupted your university studies? From a young Elizabeth Tudor facing deadly intrigue at court to a teenage Richard Burton, the rugby-obsessed son of a Welsh miner, historian Alice Loxton explores Britain’s past through the lives of eighteen figures at this crucial age. Filled with fascinating stories of royalty, explorers, writers and entertainers, Eighteen asks what lessons we can learn for modern Britain.

Rites of Passage

by Judith Flanders

Why was Victorian Britain so obsessed with death? And what impact did this have on ordinary people’s lives? In her new book, Rites of Passage, acclaimed historian Judith Flanders answers these questions and more. From mourning protocols to the bizarre customs which honoured those no longer living, Flanders offers a witty and insightful look at the cultural and social customs of a historical period we can’t help but be fascinated by.

Turning Points

by Steve Richards

In a landscape of frequent upheaval in British politics, the term 'unprecedented' is often invoked as ministers resign and inquiries ensue. Steve Richards, broadcaster and journalist, offers perspective by delving into ten pivotal moments that have moulded modern Britain. From the Suez Crisis to Covid-19, spanning 1945 to Thatcher, Richards argues that it is only with distance that we can perceive the tectonic plates shifting – and events that may seem earth-shattering in the moment might be a passing tremor with the perspective of history. Drawing on his extensive experience, he blends anecdotes and analysis to explore these key political events.

Queen of Our Times

by Robert Hardman

One of the leading writers on royalty brings us the definitive biography of Elizabeth II. Featuring new interviews with leaders from around the world, insights from friends and unparalleled access to unseen papers, Robert Hardman delves into the extraordinary life of our longest serving monarch. From war and romance to her accession to the throne at twenty-five as a mother of two, via travels, tragedy and crises, Elizabeth remained an intriguing, quietly determined figure. And this is a rounded and authoritative portrait of her.

Warriors in Scarlet

by Ian Knight

Esteemed military historian Ian Knight uses firsthand accounts to show us the reality of life for British soldiers in this era. From mundane peacetime routines to overseas deployments' challenges, Knight captures the camaraderie, floggings, and hardships. As the empire rapidly expands, the army engages in global conflicts, exposing the harsh realities of colonial warfare. Knight delves into both perspectives, as British soldiers clash with local warriors; he recreates the action, from bloody skirmishes in Southern Africa and siege warfare in New Zealand to disasters like the 1842 retreat from Kabul and Chillianwalla in the Punjab.

Royal Renegades

A tale of love and endurance, of battles and flight, of educations disrupted, the lonely death of a young princess and the wearisome experience of exile, Royal Renegades charts the fascinating story of the children of loving parents who could not protect them from the consequences of their own failings as monarchs and the forces of upheaval sweeping England.

Black and British

by David Olusoga

Winner of the 2017 PEN Hessell-Tiltman Prize.

In Black and British, award-winning historian and broadcaster David Olusoga offers readers a rich and revealing exploration of the extraordinarily long relationship between the British Isles and the people of Africa. Drawing on new genetic and genealogical research, original records, expert testimony and contemporary interviews, Black and British reaches back to Roman times and to the present, and modern Britain, showing how black British history is woven into the cultural, social and economic histories of the nation.

A History of Modern Britain

by Andrew Marr

A History of Modern Britain tackles the triumph of consumerism over politics, tracing how grand visions succumbed to celebrity culture and self-indulgence. Decade by decade, leaders' plans falter as the resilient British defy expectations. Amid invasions, financial woes, and the Cold War, the nation stands at pivotal moments, shaping global capital and migration. This narrative weaves politics, economics, and cultural shifts, delving into comedy, counterculture, and Thatcher's impact. A vibrant, candid, and comprehensive account.

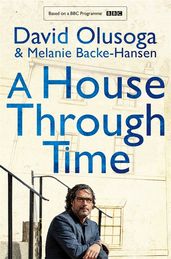

A House Through Time

Historian and award-winning TV presenter David Olusoga and research consultant Melanie Backe-Hansen offer readers the tools to explore the histories of their own homes, as well as giving a vivid history of British cities, industry, disease and class. Packed with remarkable human stories, A House Through Time is an intimate history of ordinary lives through extraordinary buildings across Britain.

The best books on European history

Voices of Victory

by Geraint Jones

In Voices of Victory, bestselling historian Geraint Jones offers a powerful and deeply personal account of the final months of the Second World War, as told by the British soldiers who lived it. Using audio interviews from the Imperial War Museums and other personal testimonies, Jones captures the raw experiences of those who fought their way through the Siegfried Line, the Reichswald forest, and across the Rhine. From harrowing combat to the liberation of Belsen, this immersive history sheds light on the human cost and courage behind the Allies’ path to victory in Europe.

Lily's Promise

by Lily Ebert

This is the moving story of Holocaust survivor Lily Ebert, written with her great-grandson Dov. When Lily was liberated at the end of the Second World War, a Jewish-American soldier handed her a banknote with the words ‘the start to a new life, good luck and happiness!’ written on it. Decades later, when Lily was 96, Dov decided to track down the family of that soldier. Lily finally told her life story to the world, from her childhood in Hungary to the deaths of her family members in Auschwitz to her new life in Israel and then London, fulfilling the promise she made to her 16-year-old self to share the horrors of the holocaust.

D-Day: The Unheard Tapes

by Geraint Jones

Marking the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings, D-Day: The Unheard Tapes is a vivid account of this pivotal moment in World War II, drawing from interviews with British, American, Canadian, German veterans, and French civilians from the Imperial War Museums and National World War II Museum archives. This powerful oral history highlights individual stories such as a forward observer on Omaha Beach, a commando racing to Pegasus Bridge, and a pilot's dramatic rescue from execution. Geraint Jones weaves these stories into a vivid narrative, allowing the voices of those who lived through the battle to shine through.

In the Midst of Civilized Europe

by Jeffrey Veidlinger

In Ukraine and Poland, over 100,000 Jews were murdered between 1918 and 1921. Jews were seen as causing the turmoil of the Russian Revolution, resulting in ordinary people killing their Jewish neighbours without impunity. Today these pogroms have been mostly forgotten, despite dominating headlines at the time, with aid workers warning that Jewish populations were in danger of extermination. Twenty years later, these predictions would prove devastatingly true. In the Midst of Civilized Europe reframes the pogroms as a turning point as renowned historian Jeffrey Veidlinger shows how this wave of genocidal violence created the conditions for the Holocaust.

The World's War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire

by David Olusoga

In this vital work, historian David Olusoga describes how Europe's Great War became the World's War, and explores the experiences and sacrifices of four million non-European, non-white people whose stories have remained too long in the shadows. A unique account of the millions of colonial troops who fought in the First World War, and why they were later air-brushed out of history, David Olusoga's meticulously researched The World's War is not to be missed.

The Glass Wall

by Max Egremont

The Glass Wall features an extraordinary cast of characters – contemporary and historical, foreign and indigenous – who have lived and fought in the Baltic and made the atmosphere of what was often thought to be western Europe’s furthest redoubt. Too often it has seemed to be the destiny of this region to be the front line of other people’s wars. By telling the stories of warriors and victims, of philosophers and Baltic Barons, of poets and artists, of rebels and emperors, and others who lived through years of turmoil and violence, Max Egremont reveals a fascinating part of Europe, on a frontier whose limits may still be in doubt.

The Greatest Escape

by Neil Churches

This is the previously untold story of the largest escape of POWs in the Second World War. Led not by officers, but by British jazz pianist Les Laws, Australian bank teller Ralph Churches and American spy Franklin Lindsay, the escape saw 106 Allied prisoners freed from a camp in Maribor, in what is now Slovenia. The book follows the escapees on their nail-biting 160-mile journey across the Alps, as they were hounded and ambushed by German soldiers. Told by Ralph Churches' son Neil, it is a fascinating tale of espionage, brutality and daring.

Eight Days at Yalta

by Diana Preston

In the last winter of World War Two, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin arrived in Yalta. Over eight remarkable days they decided on how to conduct the final stages of the war against Germany, how a defeated and how occupied Germany should be governed. Only three months later, less than a week after the German surrender, Roosevelt was dead and Churchill was writing to the new President, Harry S. Truman, of ‘an iron curtain’ that was now ‘drawn down upon [the Soviets’] front’. Meticulously researched and vividly written, in Eight Days at Yalta Diana Preston chronicles eight days that created the post-war world.

Going with the Boys

by Judith Mackrell

On the front lines of the Second World War, a contingent of female journalists were bravely waging their own battle. Barred from combat zones and faced with entrenched prejudice and bureaucratic restrictions, these women were forced to fight for the right to work on equal terms as men. Going with the Boys follows six remarkable women as their lives and careers intertwined in an intricately layered account that captures both the adversity and the vibrancy of the women’s lives as they chased down sources and narrowly dodged gunfire, as they mixed with artists and politicians like Picasso, Cocteau, and Churchill, and conducted their own tumultuous love affairs.

The Happiest Man on Earth

by Eddie Jaku

This heartbreaking yet hopeful memoir shows us how happiness can be found even in the darkest of times. In November 1938, Eddie Jaku was beaten, arrested and taken to a German concentration camp. He endured unimaginable horrors for the next seven years and lost family, friends and his country. But he survived. And because he survived, he vowed to smile every day. He now believes he is the ‘happiest man on earth’. This is his story.

1939: A People’s History

by Frederick Taylor

In the autumn of 1938, Europe believed in the promise of peace. Still reeling from the ravages of the Great War, its people were desperate to rebuild their lives in a newly safe and stable era. But only a year later, the fateful decisions of just a few men had again led Europe to war. Bestselling historian Frederick Taylor focuses on the day-to-day experiences of British and German people trapped in this disastrous chain of events and not, as is so often the case, the elite. Drawn from original sources, their voices, concerns and experiences reveal a marked disconnect between government and people.

The Women Who Flew for Hitler

by Clare Mulley

Hanna Reitsch and Melitta von Stauffenberg were talented, courageous women who fought convention to make their names in the male-dominated field of flight in 1930s Germany. With the war, both became pioneering test pilots and both were awarded the Iron Cross for service to the Third Reich. But they could not have been more different and neither woman had a good word to say for the other. In The Women Who Flew For Hitler biographer Clare Mulley gets under the skin of these two distinctive and unconventional women, against a changing backdrop of the 1936 Olympics, the Eastern Front, the Berlin Air Club, and Hitler's bunker.

France: An Adventure History

by Graham Robb

A profoundly original and endlessly entertaining history of France, from the first century BC to the present day, based on countless new discoveries and thirty years of exploring the country. Beginning with the Roman army's first encounter with the Gauls and ending with the Gilets Jaunes protests during the presidency of Emmanuel Macron, this is a vivid, living history of one of the world’s most fascinating nations.

How to Be a Refugee

by Simon May

The fate of Jews living in Hitler’s Germany is most familiar as either emigration or deportation to concentration camps. But another, much rarer, side to Jewish life at that time was denial of your origin to the point where you manage to erase almost all consciousness of it. How to Be a Refugee is Simon May’s gripping account of how three women – his mother and her two sisters – grappled with what they felt to be a lethal heritage.

Germania

by Simon Winder

There are many reasons to be fascinated by Germany: forests, architecture and fairy tales, not to mention its history and inhabitants’ penchant for very peculiar food. Our distant and often maligned cousin, this is a place in which innumerable strange characters have held power, in which a chaotic jigsaw of borders have moved about seemingly at random, and which at the dark heart of the 20th century fell into the hands of truly terrible forces. And now Simon Winder is here to tell us everything else there is to know about this mesmerizing, tortured and endlessly fascinating country.

The best books on Russian history

Blood on the Snow

by Robert Service

In his revisionist account of the origins of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Robert Service explores the factors that led to the abolition of Tsarist rule in and the rise of communism in Russia. Exploring the period from the beginning of the First World War to Lenin’s death in 1924 through primary source material, Service argues that the seeds of revolution were planted not by the workers pushing for socialism, but by the Tsar’s unpopular decision to join the war against Germany in 1914. This compelling new book by one of the foremost experts on Russian history is a must-read.

The Russian Job

by Douglas Smith

Award-winning historian Douglas Smith tells the story of how American volunteers fought famine in Bolshevik Russia, saving Lenin’s revolutionary government from chaos and millions of people from starvation. Vividly written, with a rich cast of characters and a deep understanding of the period, The Russian Job shines a bright light on this strange and shadowy moment in history.

Kremlin Winter

by Robert Service

Vladimir Putin has dominated Russian politics since Boris Yeltsin relinquished the presidency in his favour in May 2000. He served two terms as president, before himself relinquishing the post to his prime minister, Dimitri Medvedev, only to return to presidential power for a third time in 2012. Robert Service, one of the finest historians of modern Russia, brings his deep understanding of the country to this deeply insightful book about the man who leads it. This is a riveting exploration of power politics in Russia as the country faces difficulties both at home and abroad.

The Last of the Tsars

by Robert Service

In March 1917, Nicholas II, the last Tsar of All the Russias, abdicated and the dynasty that had ruled an empire for three hundred years was forced from power by revolution. In this masterful and forensic study, Robert Service examines the last year Nicholas's reign and the months between that momentous abdication and his death, with his family, in Ekaterinburg in July 1918. Drawing on the Tsar's own diaries and other hitherto unexamined contemporary records, The Last of the Tsars reveals a man who was almost entirely out of his depth, perhaps even willfully so.

The Diary of Lena Mukhina

by Lena Mukhina

In May 1941 Lena Mukhina was an ordinary teenage girl, living in Leningrad. Then, on 22 June 1941, Hitler broke his pact with Stalin and declared war on the Soviet Union. All too soon, Leningrad was besieged and life became a living hell. Lena and her family fought to stay alive; their city was starving and its citizens were dying in their hundreds of thousands. Lena records her experiences: the desperate hunt for food, the bitter cold of the Russian winter and the cruel deaths of those she loved. A remarkable account of this terrible era, The Diary of Lena Mukhina is the vivid first-hand testimony of a courageous young woman struggling to survive.

The best books on World history

Judgement at Tokyo

by Gary J. Bass

The product of a decade of research by Princeton professor Gary J. Bass, Judgement at Tokyo is a must-read for war history buffs. By honing in on the atrocities committed by Japan’s wartime leaders during the Second World War, their trial at the hands of the Allied Forces once war had ended, and the impact it had on Asia in the decades that followed, Bass shines a light on a fascinating period in Japan’s history.

The Utopians

by Anna Neima

Santiniketan-Sriniketan in India, Dartington Hall in England, Atarashiki Mura in Japan, the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in France, the Bruderhof in Germany and Trabuco College in America: six experimental communities established in the aftermath of the First World War, each aiming to change the world. Anna Neima's The Utopians is an absorbing and vivid account of these collectives and their charismatic leaders and reveals them to be full of eccentric characters, outlandish lifestyles and unchecked idealism.

Bad Land

by Jonathan Raban

Jonathan Raban's enthralling journey into the history of the Great Plains of Montana – the least populated, most uncharted region of the United States – to uncover the heart and soul of the country, with a new introduction from Jane Smiley. Bringing to life the extraordinary landscape of the prairie and the homesteaders whose dreams foundered there, and reaching through history to the present day, Bad Land uncovers the dangerous legacy of American innocence gone sour.

The Making of the Modern Middle East

by Jeremy Bowen

Jeremy Bowen, the International Editor of the BBC, has been covering the Middle East since 1989 and is uniquely placed to explain its complex past and its troubled present. In The Making of the Modern Middle East, Bowen takes us on a journey across the Middle East and through its history. He meets ordinary men and women on the front line, their leaders, whether brutal or benign, and he explores the power games that have so often wreaked devastation on civilian populations as those leaders, whatever their motives, jostle for political, religious and economic control.

Until Proven Safe

by Geoff Manaugh

Quarantine has shaped our world, yet it remains both feared and misunderstood. It is our most powerful response to uncertainty, but it operates through an assumption of guilt: in quarantine, we are considered infectious until proven safe. Until Proven Safe tracks the history and future of quarantine around the globe, chasing the story of emergency isolation through time and space. Part travelogue, part intellectual history – this is a book as compelling as it is definitive, and one that could not be more urgent or timely.

Falling Off the Edge

by Alex Perry

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, international corporations and governments have embraced the idea of a global village: a shrinking, booming world in which everyone benefits. What if that's not the case? Foreign correspondent, Alex Perry, travels from the South China Sea to the highlands of Afghanistan to see first-hand globalization at the sharp end. Whether it's Shenzen, China's boom city where sweatshops pay under-age workers less than $4 a day, or Bombay, where the gap between rich and poor means million-dollar apartments overlook million-people slums, Perry demonstrates that for every winner in our new world, there are hundreds of millions of losers.

India After Gandhi

by Ramachandra Guha

Born against a background of privation and civil war, divided along lines of caste, class, language and religion, independent India emerged, somehow, as a united and democratic country. Ramachandra Guha’s hugely acclaimed book tells the full story – the pain and the struggle, the humiliations and the glories – of the world’s largest and least likely democracy. Massively researched and elegantly written, India After Gandhi is a remarkable account of India’s rebirth, and a work already hailed as a masterpiece of single-volume history.

India

by V.S. Naipaul

Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul first visited India in 1962, hoping to settle the ghosts of a painful ancestral past. An Area of Darkness chronicles his initial visit as estrangement gives way to connections and conversations. Prompted by the Emergency of 1975, India: A Wounded Civilization presents an intellectual portrait of a country whose people are no longer so willing to bear witness. India: A Million Mutinies Now captures a panorama of voices fifteen years later, at another moment of national upheaval. Born of Naipaul’s wish to see the homeland from which he was twice displaced, India emerges as an invaluable account of a nation in times of dramatic change.

The Best of Times, The Worst of Times

by Michael Burleigh

In a forensic examination of the world we now live in, acclaimed historian Michael Burleigh sets out to answer: are we living in the best, or the worst of times? Who could have imagined that China would champion globalization and lead the battle on climate change? Or that post-Soviet Russia might present a greater threat to the world’s stability than ISIS? And while we may be on the cusp of still more dramatic change, perhaps the risks will – in time – bring not only change but a wholly positive transformation.

The best books on the history of religion

Heresy

by Catherine Nixey

‘In the beginning was the Word,’ says the Gospel of John. This sentence – and the words of all four gospels – is central to the teachings of the Christian church and has shaped the Western mind. Yet in the years after the death of Christ there was not any consensus as to who Jesus was or why he had mattered – in fact, there were many different Jesuses. Moreover, there were many other saviours, but as Christianity spread, they were pronounced unacceptable – even heretical – and they faded from view. Now, in Heresy, Catherine Nixey tells their extraordinary story, one of contingency, chance and plurality. It is a story about what might have been.

God: An Anatomy

by Francesca Stavrakopoulou

Three thousand years ago, in the region we now call Israel and Palestine, people worshipped an array of deities led by a god called El. El had seventy children, all of whom were gods themselves; one of these children, Yahweh, fought humans and monsters and eventually evolved into the God of the great monotheistic faiths. The history of God in culture stretches back centuries before the Bible was written. Elegantly written and fiercely argued, Professor Francesca Stavrakopoulou provides a fascinating analysis of God’s cultural DNA, and in the process explores the founding principles of Western culture.

Lost Islamic History: Reclaiming Muslim Civilisation from the Past

by Firas Alkhateeb

In the bestselling work Lost Islamic History, Firas Alkhateeb seeks to shine a new light on the contributions of Muslim thinkers, scientists and theologians, not to mention statesmen and soldiers, which have been overlooked for millennia. This important book rescues from oblivion a forgotten past, charting its narrative from Muhammad to modern-day nation-states. From Abbasids and Ottomans to Mughals and West African kings, Alkhateeb sketches key personalities, inventions and historical episodes to show the monumental impact of Islam on global society and culture.

The best books on historical figures

The Three Mothers

by Anna Malaika Tubbs

These are the stories of Louise Little, Alberta King, and Berdis Baldwin – the mothers of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Baldwin, respectively. Anna Malaika Tubbs' vital history book is part-biography, part-manifesto, and centers on three remarkable women who were traumatized by the country that both they and their sons would go onto change irrevocably. This essential celebration of their lives and contributions to the civil rights movement serves to ensure that their stories are not erased and gives credit where it is long overdue.

Dutch Light

by Hugh Aldersey-Williams

Dutch Light is both a vivid account of the remarkable life and career of Christiaan Huygens and the story of the birth of modern science as we know it today. Christiaan Huygens was a true polymath and Europe’s greatest scientist during the latter half of the seventeenth century, developing the theory of light travelling as a wave, inventing the mechanism for the pendulum clock, and discovering the rings of Saturn – via a telescope that he had also invented.

Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands

by Mary Seacole

Mary Seacole was a fiercely independent self-funded entrepreneur from Jamaica. A trained nurse, she was desperate to offer help during the Crimean War, but was denied work by officials and by Florence Nightingale. Mary knew what she wanted to achieve and wouldn’t let anything stand in her way, so she set up her famous hotel for British soldiers, offering respite from the front line. Wonderful Adventures of Mrs Seacole in Many Lands is her gutsy autobiography.

Machiavelli

by Alexander Lee

Thanks to the invidious reputation of his most famous work, The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli exerts a unique hold over the popular imagination. But was Machiavelli as sinister as he is often thought to be? Might he not have been an infinitely more sympathetic figure, prone to political missteps, professional failures and personal dramas? This riveting biography reveals the man behind the myth, following him from cradle to grave, from the great halls of Renaissance Florence to the court of the Borgia pope, Alexander VI, from the dungeons of the Stinche prison to the Rucellai gardens, where he would begin work on some of his last great works.