Synopsis

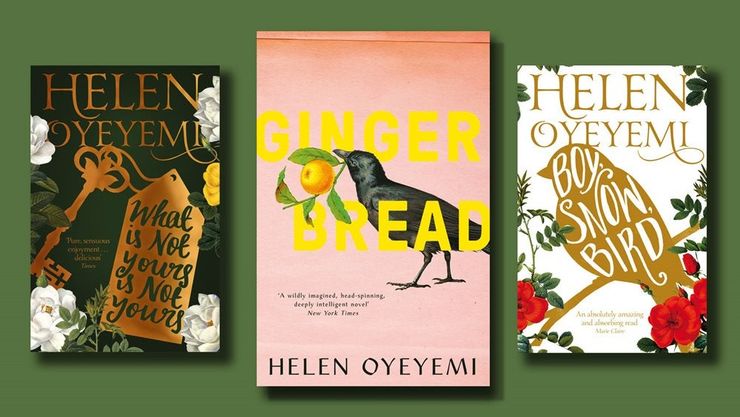

The fifth novel from award-winning author Helen Oyeyemi, named one of Granta's best young British novelists. A retelling of the Snow White myth, Boy, Snow, Bird is a deeply moving novel about an unbreakable bond . . .

BOY Novak turns twenty and decides to try for a brand-new life. Flax Hill, Massachusetts, isn't exactly a welcoming town, but it does have the virtue of being the last stop on the bus route she took from New York. Flax Hill is also the hometown of Arturo Whitman – craftsman, widower, and father of Snow.

SNOW is mild-mannered, radiant and deeply cherished – exactly the sort of little girl Boy never was, and Boy is utterly beguiled by her. If Snow displays a certain inscrutability at times, that's simply a characteristic she shares with her father, harmless until Boy gives birth to Snow's sister, Bird.

When BIRD is born Boy is forced to re-evaluate the image Arturo's family have presented to her, and Boy, Snow and Bird are broken apart.

Sparkling with wit and vibrancy, Boy, Snow, Bird is a novel about three women and the strange connection between them. It confirms Helen Oyeyemi's place as one of the most original and dynamic literary voices of her generation.

Details

Reviews

A spellbinding, wholly original look at families and the secrets they keep . . . An absolutely amazing and absorbing read

Gloriously unsettling . . . it's clearly the book she's been waiting for . . . the greatest joy of reading Oyeyemi will always be style: jagged and capricious at moments, lush and rippled at others, always singular, like the voice-over of a fever dream.

Boy, Snow, Bird is a haunting, tender portrait of three women from one of our generation's most talented literary writers

Boy, Snow, Bird is among my favorite new releases for this year already. A retelling of the Snow White fairy-tale that focuses on race, it's a sensitive, intelligent treatment of a subject most fiction still sidesteps. Fans of Adichie's Americanah who also like a little fantasy in their coffee will be enchanted, I think.