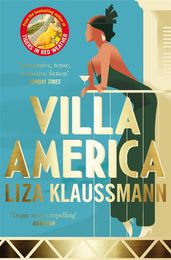

Synopsis

'Immersive, tense, seductive' – Sunday Times

'Unputdownable' – Sunday Express

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Pablo Picasso, Cole and Linda Porter, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos - all are summer guests of Gerald and Sara Murphy. Visionary, misunderstood, and from vastly different backgrounds, the Murphys met and married young, and set forth to create a beautiful world. They alight on Villa America: their coastal oasis of artistic genius, debauched parties, impeccable style and flamboyant imagination. But before long, a stranger enters into their relationship, and their marriage must accommodate an intensity that neither had forseen. When tragedy strikes, their friends reach out to them, but the golden bowl is shattered, and neither Gerald nor Sara will ever be the same.

Ravishing, heart-breaking, and written with enviable poise, Villa America delivers on all the promise of Liza Klaussmann's bestselling debut, Tigers in Red Weather. It is an overwhelming, unforgettable novel.

Details

Reviews

Klaussmann writes beautifully . . . [A] gorgeous, melancholy novel.

Immersive . . . a memorably tense, seductive fiction from many perspectives

Glitteringly alive.

A brilliant novel about love in all its forms . . . A deeply moving portrait of a marriage and of a world.