Mona Chollet and Sally Hinchcliffe on reclaiming witchcraft

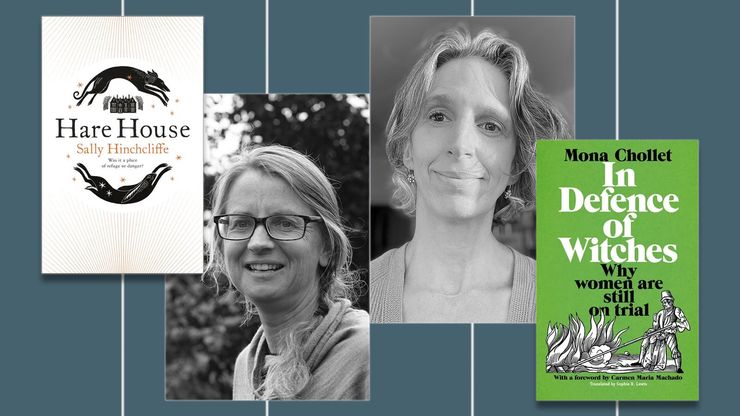

Two authors and leading voices on portrayals of witchcraft, both modern and historical, discuss the changing image of the witch in society and whether women are still being put on trial by pervasive social misogyny.

Who, or what, is a ‘witch’?

The meaning of the word is ever-changing. Today, witches are upheld as strong and independent role models in children’s literature, but in western culture ideas around the mystical and supernatural are now as far-fetched or harmless instead of the serious accusations they once were.

Witchcraft isn't always seen this way. The term ‘witch’ carries a long, controversial, and violent history that stretches back over centuries. Accusations of witchcraft are still taken very seriously in some parts of the world, and is still a crime in many cultures.

Mona Chollet is a journalist and author of In Defence of Witches, where the image of the witch is recast as a empowering role model to women today. By examining the narrow limits society imposes on women and comparing these with historical witch hunts, Mona shows just how many different things a woman can choose to be.

The idea of the modern witch is explored further in Hare House, an eerie novel by Sally Hinchcliffe about witchcraft in rural Scotland. Inspired by the real-life historical confessions of accused 'witches', the book is a suspense-filled story about madness, superstition and the balance between psychology and witchcraft.

Here, both authors discuss alternate reality where the witch trials didn't happen, the 'good witch' trope in children's literature, and the 'witches' of today who escape the conformity and expectations of society.

For more mystical reads, discover the best books about witches.

Mona Chollet: How did you become interested in the Scottish witch hunts?

Sally Hinchcliffe: It was after I moved up here to Dumfries and Galloway which is one of the places with quite intense witch persecution and a lot of history about it. There is a waterfall near our house where there was a legend that suspected witches would be closed up in a barrel and sent down the waterfall as a test.

It was nonsense (or at least there’s no evidence of it), but it got me interested in the real history and I started researching some of the witchcraft trials – all the records were kept, including the statements of the women involved. It was really interesting to hear voices from the 17th century – people you wouldn’t normally hear from.

What started your interest?

MC: Well, for me it was from a very different point of view. I’ve always been fascinated by (fictional) witches, but I had never thought of writing a book about them. I was hesitating between a few topics at the time: I wanted to write about childfree women; I also wanted to write about age and its social meaning for women. And one day, I realized childfree women and ageing women were all kinds of witches!

‘I wanted to write about childfree women; I also wanted to write about age and its social meaning for women. And one day, I realized childfree women and ageing women were all kinds of witches.’

MC: Was the test with the waterfall the usual one? If she floats, she’s a witch, and if she drowns, she’s innocent, but she’s dead anyway?

SH: Yes! That always seemed so unfair to me as a child. But it wasn’t something that comes up at all in the written record, so it seems to have been the product of someone’s overheated imagination.

MC: I always thought it reflected so well the way women can never be right regarding social norms and requirements.

SH: Absolutely, it struck me when reading your book that it could equally have been called ‘In Defence of Women’. Do you think we’re still in a position where we can’t win, damned if we do, and damned if we don’t?

MC: Yes, I think it’s still very much the same. For example, if you try to look young, people criticize you for being so shallow, or because the surgery shows, whatever; and if you look old, there is always this kind of hatred. We can’t win, so we’d better not care at all!

SH: I wonder if we are starting to change how that works, with the younger generation? I’m thinking about people like Billie Eilish, who seems so able to reject a lot of the expectations of a girl of her age.

MC: Yes, I’m very impressed by the way many young women seem lucid about what it’s like to be a woman and the traps and dangers of social expectations. I hope they will contribute to changing this culture!

‘I’m very impressed by the way many young women seem lucid about what it’s like to be a woman and the traps and dangers of social expectations.’

MC: I read that in some Scottish towns there was a man who was called to search women’s bodies for the Devil’s mark, have you read about it?

SH: Yes, the witch pricker. That was the test that was used, rather than trial by water. It is interesting because there was a lot of ‘due process’ in the witchcraft trials - there would be a massive witch panic when waves of accusations would go through whole neighbourhoods with everyone swept up in it, but then when it came to the trial and punishment, there had to be the same standards of evidence as for any other crime. So women would be interrogated and sometimes they would confess (as well you might with someone poking you with a needle and keeping you up all night). But equally, quite a lot of people were acquitted.

That was where I became interested, because the ‘dittays’ which were the affidavits of the witnesses and the accused, are all recorded so you get to hear about people’s real lives – it’s not this very remote medieval society.

MC: It must have been fascinating to discover the direct sources. Did it change the ideas you had about these events? Or the way you look at today’s society?

SH: Completely. A lot of what I read from secondary sources were Victorians who were very judgemental about the witch panics and who were willing to believe anything, hence the witch in the barrel.

But the reality was much more judicial, and that makes it worse in a way. You think about how the Nazis kept all their records and were so ordered and bureaucratic in their crimes; these weren’t just people caught up in madness, it was the full force of the law being used in a very measured way.

The other thing that intrigued me was that a few of the accusers were teenage girls who you might think of as the most powerless in society but they could turn into an avenging force and trigger a witch panic. Do you think we’re too quick to forget that women were also accusers as well as the accused?

MC: I don’t know, but it doesn’t surprise me. Many women in history have made the choice to stay on the side of power! They thought they would be better off this way, and it’s not always a bad choice. It’s a way to gain some power for yourself. When women have so much to lose when they rebel, it’s understandable, even if I think it’s sad.

SH: A lot of the accusers, in that case, would be wards or orphans, with a dubious status in the household, so this could be a way of cementing that position.

MC: Very interesting, and I guess sometimes fear could encourage women to accuse other women first! Before being accused themselves. It must have been such a strange and frightening atmosphere, as you say, with this mixture of complete madness and rationality in the trials.

SH: I was interested too in the women who confessed. I’m sure most of it was under duress, and there were certain stock phrases – as you mentioned – that were used because that was what the interrogators wanted to hear, but I wonder too if there were women who wanted to have power over their neighbours and to be able to wield ill-wishing against people who had done them wrong?

MC: It must have served all kinds of interests and purposes, and caused so much injustice. Don’t you think it must have had a disciplinary effect on all women? Censoring some behaviours and encouraging other attitudes?

SH: Absolutely, I can see how it would have been deadening.

‘It’s so tantalising to think that there could have been another history where women weren’t as subjugated for so long.’

SH: I was really interested in the women’s spaces you mentioned where women who were not under the dominion of men could make a living for themselves and thrive, and how the witch panics were used as a way to sweep those away. It’s so tantalising to think that there could have been another history where women weren’t as subjugated for so long. Do you think it’s inevitable that these sort of women’s spaces will get attacked - that as soon as women start to accrue a bit of power, there is a backlash?

MC: I hope not, or at least not always such a violent backlash, but there was one at the time, for sure. I’m sure the witch hunts shaped the way we look at independent women until today! For me, the spinster with her cat is clearly a ghost of the witch with her familiar. She’s looked at with a kind of pity, but I’m sure there is fear behind this pity!

‘For me, the spinster with her cat is clearly a ghost of the witch with her familiar. She’s looked at with a kind of pity, but I’m sure there is fear behind this pity!’

SH: Yet the ‘good witch’ is quite a powerful trope in children’s literature, especially appealing to girls – the ‘wise woman’.

MC: Yes! I think we have to thank the feminists who reversed the stigma, in a way. It was very helpful for me too when I decided to write about these stereotypes against women. At first my writing was a little whiny (is that the correct word?!) and defensive, but it was very empowering to identify the witch as the dominant figure.

What do you think of the way this figure of the witch evolved through the centuries?

SH: It’s an interesting question. I think you identify The Wizard of Oz as the first piece of writing with a ‘good’ witch, and since then she’s been quite a common figure. I suppose also there are cultures where wise women haven’t been feared and persecuted?

MC: That’s a good question! Unfortunately, I know more about cultures where it’s still the case, in more or less violent ways. In Nigeria, this year, 30 women were burnt alive as witches. It seems very common.

SH: When I lived in Eswatini (Swaziland) it was sometimes talked about, but I’ve wondered if the European colonialists brought their own ideas into Africa and somehow welded them onto indigenous culture. Just because we use the same word, doesn’t mean it’s the same thing.

MC: Yes, you’re right, absolutely. Did your interest in witchcraft start when you were living there?

SH: It wasn’t something I really picked up on at the time, but as I started to explore it in my fiction it came back to me, the fact that it seems like witchcraft – or at least the fear of witchcraft – is pervasive across cultures. We all want to find someone or something to blame and the more arbitrary and unfair life is, the easier it is to find something or someone to point the finger at.

We only have to look at how we’ve reacted to COVID to see how close to the surface our irrationality is!

MC: Yes, exactly! What struck me in the history of witch hunts is how it was a perfect scapegoat mechanism. And it’s really terrifying, because it’s unstoppable. You can’t discuss things with people who, deeply, are only looking for a scapegoat.

SH: Yes, imagine if all your cattle are dying or your crops have failed. It would almost be wrong not to persecute the person who was seen muttering curses at them, if that would help save the village.

MC: And, it doesn’t change through history. That was the most troubling part of writing this book, being confronted with this dark aspect of human societies.

SH: Do you think the good witch, the wise woman, offers a path out? If you look at the younger generation who have been raised on those stories, they’re not interested in buying into the whole ‘witch hunt’ narrative – they are primed to defend the outsider, in a way.

‘The younger generation . . . they’re not interested in buying into the whole ‘witch hunt’ narrative – they are primed to defend the outsider.’

MC: It’s a very beautiful idea. I love the way the ‘good witch’ becomes more and more refined and interesting. You mentioned The Wizard of Oz, and yes, Glinda was the first ‘good witch’ (I think), but she looked very much like a fairy! As we weren’t able at the time to imagine a real good witch. But we’ve been progressing since then! That’s why I love Flutter Mildweather from The Glassblower’s Children so much. She’s old, she’s not pretty or thin or blonde, and she really is a good witch! You want to be her!

SH: I just reread A Wrinkle in Time, and the women there kind of come across as witches, although they’re something much stranger. But it was interesting how they’re a little scatty, a bit disorganised, as if they are hiding their real power under a layer of fluff. Even the good witches may have to dissemble a bit if they’re not going to be driven out.

MC: Yes, it might be a kind of strategy. Sometimes witches are not even aware of their power, as they have been looked down upon for so long. It takes time to master it.

SH: I think given the mess we’ve got ourselves into being led by confident men who overestimate their powers, perhaps it’s the turn of the uncertain witches to have a go.

MC: I couldn’t agree more! We definitely need uncertainty. It has a beauty in it.

Hare House

by Sally Hinchcliffe

On a crisp autumn day a woman travels to London, having left her post at a London girls school in murky circumstances. She starts to explore the land around her cottage on the isolated Hare House estate, walking the moors and woodland. And she begins to hear unsettling stories, of witches, strange clay figures, and young men scared out of their wits. Having made friends with her landlord Grant and his sister Cass, doubts begin to descend. And when a snowfall traps the inhabitants of the house together, the tension escalates . . .

In Defence of Witches

Who is a witch? In Defence of Witches recasts the term 'witch' into a powerful role model to women today, as an emblem of power free to exist beyond the narrow limits society imposes on women.

Witches are everywhere, whether they are casting spells on Donald Trump or posting photos of their crystal-adorned altar on Instagram. But who were the predecessors of these modern witches? Historically accused of witchcraft, often meeting violent ends, many types of women have been censored, eliminated, repressed, over the centuries. Mona Chollet shows that by considering the lives of those who dared to live differently, we can learn more about the richness of roles available, just how many different things a woman can choose to be.