Six of the most iconic queer heroes from literature

Which queer heroes (or anti-heroes) have stayed with you long past the last page? For LGBTQIA+ History Month, James Hodge – English lecturer and outstanding advocate for improved LGBTQIA+ education in classrooms – reveals his most iconic queer heroes from literature.

Growing up gay, representation in literature mattered. When I first came out, literature allowed me – a smalltown boy – to explore the many colours of that rainbow world beyond the white picket fences of my childhood. I was soon to befriend many a character who was ‘just like me’ – Maupin’s Michael Tolliver danced with me in the nightclubs of San Francisco; Aciman’s Elio Perlman lazed beside me by the swimming pool in Italy, and Hollinghurst’s Nick Guest took me on a wander through the cruising grounds of Hampstead Heath. Literature was my key to navigating the future – it gave me role models to look up to; an understanding of gay culture and community; and warned me of the challenges I might face growing up different.

‘Literature was my key to navigating the future – it gave me role models to look up to; an understanding of gay culture and community; and warned me of the challenges I might face growing up different.’

However, with LGBT now expanded to include a Q-I-A and a '+', society’s understanding of gender and sexuality is more open and dynamic than ever. Queer, once a beating stick used to attack gay and bisexual men and women, has become a tool of power wielded by us to break the limitations of identities. It is a new way of looking – breaking down binaries and shattering stereotypes in order to allow us to live more freely and authentically beyond the norm. This queer lens has changed the way we read, allowing us to look beyond the immediately gay protagonists of past literature, and to discover all shapes and sizes of queer characters lurking in the shadows.

A Little Life

by Hanya Yanagihara

When I picked up A Little Life, I had no idea that I was reading a queer novel. It wasn’t marketed with a rainbow-colored cover; it wasn’t hidden in the LGBTQ+ section of the bookshop. Indeed, the power of Yanaghihara’s novel is the refusal to immediately label its characters. It soon becomes evident that protagonist Jude has a tragic history, but the beautiful relationship that grows between he and his best friend is one that is hugely moving. Queerness, Yanagihara tells us, transcends words – love can blossom anywhere regardless of our gender.

‘When I picked up A Little Life, I had no idea that I was reading a queer novel. It wasn’t marketed with a rainbow-colored cover; it wasn’t hidden in the LGBTQ+ section of the bookshop.’

Paul Takes the Form of A Mortal Girl

From the moment I read the title of Lawlor’s debut novel, I knew that I was going on an adventure, the sharp juxtaposition between name and gender immediately challenging my understanding of the protagonist. A shape-shifter of sorts, Paul morphs across the spectrum of sexes and genders to provide insight into the different experiences queer people. Unpindownable, Lawlor achieves something brilliant in the way that our reading is consistently repositioned, forced to change perspective and understand how LGBTQIA+ history was experienced from different angles within our community.

The Mercies

by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Is there anything queerer than witchcraft? In Hargrave’s novel The Mercies, the Finnish island of Vardø becomes matriarchal after the men on the island die during the Christmas Eve storm of 1617. A queer power develops here, demonstrated by the women’s thriving when they pull together and unite in order to survive. However, the strength of Hargrave’s celebration of the queer feminine is by her recognising the tensions within the community itself – a power struggle between the religious Toril Knudsdatter and the more progressive Kirsten Sørensdatter. The very definition of womanhood is debated and destabilized by the spectrum of women themselves. The love story between Ursa and Maren only further demonstrates how queer love can blossom when society’s rules are broken.

The Line of Beauty

by Alan Hollinghurst

I have already mentioned Hollinghurst’s protagonist Nick Guest in what might be my favourite gay novel of all time, but on revisiting, the true queer hero of the text is Nick’s first love, Leo Charles. Where Nick chooses to blend in with his adoptive family the Feddens and keeps his sexuality a badly-hidden secret, Leo is queer and proud from the offset. Immediately distinguished by his race, Leo not only has the challenge of being gay in the 1980s but also those of being black in Thatcherite Britain. If to be queer is to understand the intersections of our identity – to proudly embrace being ‘other’ – Leo is a hero for his proud promiscuity, street-smart attitude and cocky, playful nature.

American Psycho

by Bret Easton Ellis

When Easton Ellis’ iconic novel was first released, it was banned. Not because of gay content, however, but due to its shocking and misogynistic portrayal of violence towards women. Thirty years later and the novel remains a cult classic, perhaps because if you read between the lines, there may be more to Patrick Bateman that it first seems. Yes, he is undeniably a sick mind who enacts the most terrible of acts on many a victim, but where does this drive come from? Is the highly disciplined and controlled narrator in fact repressing his homosexual desires, suggested by his admiring description of other male characters? Is his murdering of sex workers a rejection of heterosexuality? And ultimately, did any of the novel's events happen or is he simply traumatized? It’s all dependent on your reading of that final passage.

The Great Gatsby

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

It’s one of the greatest love stories of all time, but is Fitzgerald’s novella purely about the love between the eponymous Gatsby and his sweetheart Daisy, or are there other desires bubbling beneath the surface? Nick Carraway, the peripheral narrator, may present as heterosexual in his curious relationship with Jordan Baker, but it is his obsession with Gatsby and his need to share Gatsby’s story that suggests to many that there is a deeper love that cannot be spoken here. Nick’s admiring descriptions of Gatsby, his willingness to do anything to help him, and the way that he can never let Gatsby go, complicates their relationship into one that is queer and unable to be labelled.

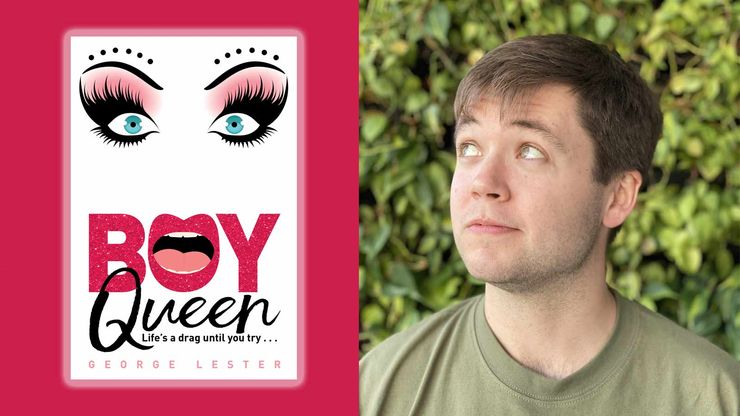

Discover the best queer YA books for all ages