General

The best rugby books and autobiographies to read now

24 of the best popular science books

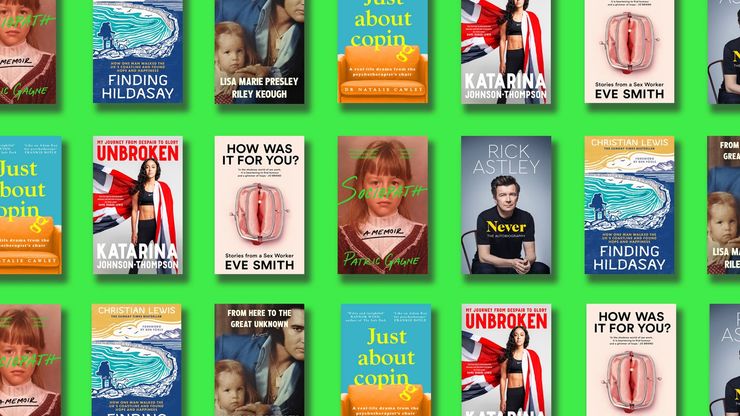

The best non-fiction books of 2026, and all time

50 best autobiographies & biographies of all time

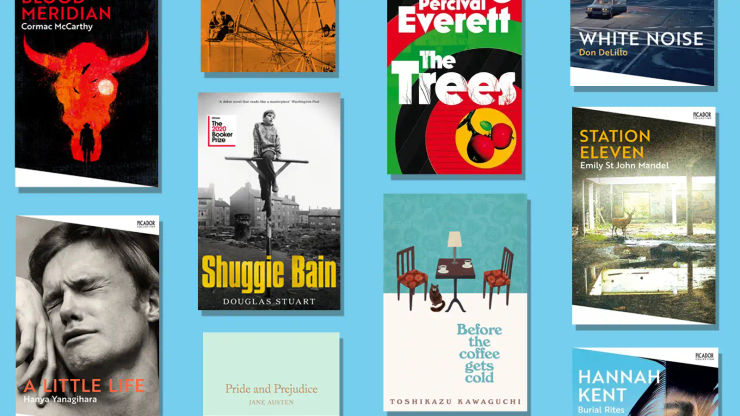

Must reads: 50 best books of all time

The best gateway books to help get you into a new genre in 2026

The best sports autobiographies and books

The best books for men, recommended by publishing insiders

Brilliant Christmas gift ideas: the best books to give in 2025

Nothing is as it seems: 9 must-read exposés

The best political books to read right now

Can money buy happiness?