The untold story of Bawdsey Manor and the invention of radar

The story of Bawsdey Manor and the courageous women who worked as radar operators during World War Two is still largely unknown. Here Liz Trenow, the author of Under a Wartime Sky, shares the history behind her new book.

While the story of Bletchley Park and the codebreakers who worked there – brought to life in the film The Imitation Game starring Benedict Cumberbatch – is widely known, the story of Bawdsey Manor has been largely forgotten. But author Liz Trenow has always been fascinated by the events that occurred there, and which inspired her novel Under a Wartime Sky. Here, she explores the history of the manor and the vital radar technology that was invented there.

Don't miss our edits of WWII stories and the best historical fiction books of all time.

This year – which marks the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain – many thousands of visitors from all over the world will flock to the popular tourist attraction of Bletchley Park, to learn how codebreakers helped to win World War Two.

Sadly, what is almost forgotten is the equally vital work of the scientists who developed radar – then known as Radio Direction Finding – and the hundreds of operators, mainly women, who worked day and night, up and down the coasts of Britain, to track the approach of enemy planes. During the Battle of Britain, radar delivered crucial intelligence, enabling the RAF to overcome the Luftwaffe’s 2,400 planes with just 640 of our own.

I have been fascinated by this story ever since I was a child, and my new novel, Under a Wartime Sky, was inspired by real-life people and events, and especially the place where radar began, in a fairy-tale mansion in a remote part of the Suffolk coast.

My father was a keen dinghy racer and as children we spent many anxious hours watching him from the shingle at Felixstowe Ferry. Across the river, the gothic towers of Bawdsey Manor peeped enticingly above the pines, although it was still firmly out of bounds. Several decades later, some friends bought the place from the Ministry of Defence to set up an English language school. We visited often and soon fell in love with it.

The manor and estate – including a farm and staff houses – was built by a Victorian millionaire, William Cuthbert Quilter MP, as his ‘seaside home’. His wife, Lady Quilter, created extensive formal gardens including a cliff path, using an artificial rock called pulhamite.

In 1936 Winston Churchill asked the physicist Sir Robert Watson-Watt to develop a ‘death beam’ or a ‘magic eye’ to counter the growing threat of German airborne aggression. Under the cloak of utmost secrecy, he and a small team of brilliant scientists moved into the manor. Stables and outbuildings were converted into workshops and the first receiver and transmitter towers were built. Just eighteen months later, RAF Bawdsey became the first fully operational radar station in the world.

As the technology developed, dozens of similar stations with their distinctive towers were hastily constructed all along the south and east coasts of Britain. Watson-Watt – whose mother had been an early feminist – shocked everyone by declaring that his team should recruit and train women as radar operators because they had better concentration, more patience and the delicate touch needed for the sensitive instruments.

After war was declared, thousands of young women joined the newly created Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and were put through rigorous aptitude tests. Because of the secrecy, those chosen to be radar operators had little idea of what this meant until they started the intensive period of highly technical training. Even then many failed to make the grade.

The work was hard and demanding – intense concentration and nerves of steel were required. Shifts operated day and night, scanning the skies for signs of enemy aircraft and tracking our own during dog fights. Later, the operations provided a vital early-warning system against bombing raids. It was dangerous – the stations were highly vulnerable in their coastal positions and easily identifiable by their tall masts. Several suffered disastrous bombing, but the women never deserted their posts.

As with the codebreakers of Bletchley Park, the work of the scientists who developed radar and the women who operated it remained an official secret for many decades. Even now, very little is known about their critical role in helping to win the war.

The Bawdsey Radar Trust is working hard to change this. The small museum, largely run by volunteers in a former transmitter block, explains how radar began, and how influential it was and still is today. Radar developed into microwave technology which has thousands of applications in our everyday lives: it’s used in speed cameras and air traffic control, as well as in space. A millennium-funded project recorded fascinating oral histories of the experiences of the women and men who worked at the manor, and the museum recently won the Suffolk Small Museum award. Find out more at www.bawdseyradar.org.uk.

The manor itself is still in private hands (it’s now a children’s holiday centre) and is not open to the public.

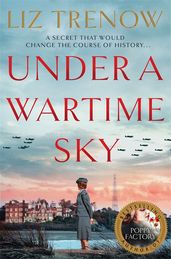

Under a Wartime Sky

by Liz Trenow

In 1936, as the threat of war hangs over Europe, Churchill gathers the brightest minds in Britain together in a Suffolk country house. Their mission? To invent the technology that could mean victory for the Allies. Vic, a shy physicist, has finally found a place where he belongs, and when Kath is recruited to operate the top-secret system they form an unlikely friendship as bombs fall over Britain.