How the Gladiators furthered our knowledge of the human body

The Map of Knowledge follows the ideas of some of history's greatest scientists from antiquity to the modern world. Here, author Violet Moller explains how our understanding of human anatomy originated with the work of Galen and his treatment of gladiators' wounds . . .

In her debut book, The Map of Knowledge, Violet Moller traces the journey taken by the ideas of Euclid, Galen and Ptolemy - three of history's greatest scientific minds. Here, she explains how our modern understanding of human anatomy originated with Galen's work tending to the wounds of Roman gladiators.

Dissecting human bodies isn’t many people’s idea of fun and for several centuries it was not only socially unacceptable, but illegal as well. As a result, progress in the study of anatomy slowed pretty much to a standstill. To put it simply, without being able to look inside a body, it was very difficult to discover how the complex physiological systems and organs functioned. While some civilisations, the Egyptians in particular, practiced embalming – a process that involved removing certain organs after death and storing them in special ceremonial jars – this does not seem to have provided much specific anatomical knowledge. Most ancient anatomical information came from the glimpses into the human body offered by the treatment of wounds, supplemented with what was learnt from dissecting animals. Opening up human corpses was always a problematic idea - not only did it risk spreading disease and making the dissector unclean, it was also considered impious and totally unacceptable in many societies.

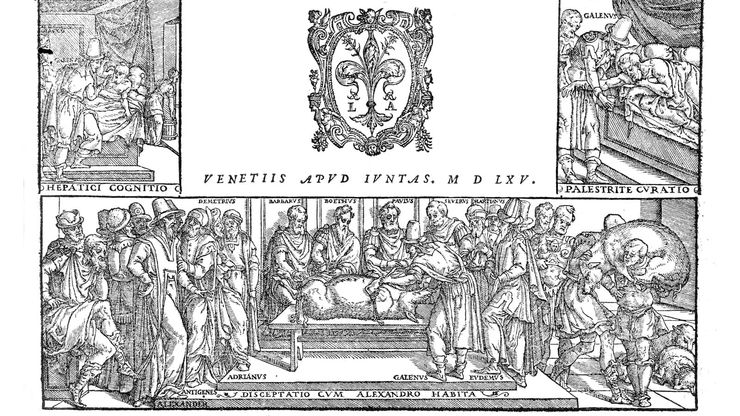

In spite of this, human dissection (and more shockingly, vivisection) was carried out in the last few centuries BC by doctors in Alexandria, where the Ptolemaic kings were prepared to go to great lengths to transform their city into the most important centre of learning on earth. This practice died out when the Romans, who had decreed human dissection unlawful several decades earlier, conquered the city in 80BC. Galen (129-200AD), the most successful and prolific medical practitioner in the whole of antiquity, wrote extensively on anatomy and human physiology; works which defined the discipline for over a millennium. However, as far as we know, he never dissected a human corpse. Instead, he spent years working at a school for gladiators, treating all kinds of wounds, and learning a huge amount about anatomy in the process. He supplemented this knowledge by dissecting animals (as shown in the image above) – especially pigs and barbary apes whose physiologies are perhaps surprisingly similar to ours. With his natural flair for drama, Galen’s public dissections and vivisections were hot ticket events for the Roman elite, who flocked to watch him demonstrating anatomy in all its gruesome detail.

For the next millennium, knowledge of anatomy was based almost entirely on Galen’s books, human dissection does not seem to have occurred at all. The mantle of scientific enquiry was taken up by Muslim scholars in the eighth and ninth centuries, but their faith discouraged dissection and dictated that a corpse should be cremated as soon as possible after death. So, while scholars in the Medieval Arab world made huge contributions to many areas of medical science, anatomy was not one of them. Meanwhile in Europe, the Southern Italian seaside town of Salerno became the first great centre of medicine in the Middle Ages. Physicians there began dissecting as part of their studies, but (initially at least) they only used the corpses of pigs.

Human dissection begun again in earnest at Bologna University in the late 13th century when anatomy and anatomizing (the process of dissecting a body) were introduced as a fundamental part of the medical curriculum. As in Alexandria, the corpses used were executed criminals – a tradition that would continue for several centuries and explains why anatomy centred on the male body – far fewer female criminals were put to death.

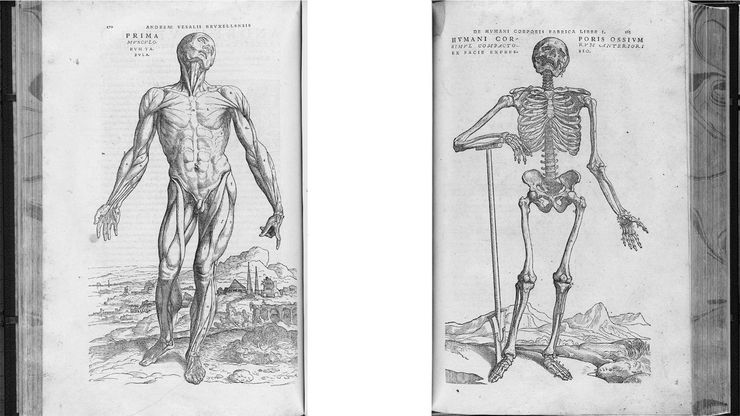

Throughout this period, anatomy was still totally dependent on Galen, who was held up as an absolute authority, in spite of the obvious inaccuracies in his works. It wasn’t until the mid-sixteenth century that a physician came along who felt able to question and correct Galenic anatomy. His name was Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). Like Galen, Vesalius was prodigiously talented; by the tender age of 20 he was already extremely knowledgeable in Greek, Latin and medicine, and perhaps most important of all, he was a genius at anatomizing cadavers. Apparently, he made friends with the local judge in Padua where he worked at the university to ensure he had a ready supply of bodies.

As his work progressed, Vesalius noticed more and more mistakes in Galenic anatomy – for example, the inclusion of an extra vertebra that was present in apes but not in humans – but it took him a long time to accept that what he was seeing in front of him was correct and that Galen was wrong. This seems strange to us today, but during the Renaissance, the idea that Classical scholars had access to higher knowledge was all-pervasive, and Vesalius had to work hard to persuade his colleagues that his new anatomy should replace Galen’s. He did this in 1543 by detailing his discoveries in a ground-breaking book, De humani corporis fabrica, which he filled with stunning images showing every layer and detail of the human body. From this moment on, the study of anatomy was transformed. Human dissection has continued ever since; it remains a fundamental part of medical education, but these days the cadavers have been voluntarily donated to medical science, rather than taken from the executioner’s platform.

The Map of Knowledge

The Map of Knowledge traces the journey of the ideas of three of history’s greatest scientists, Euclid, Galen and Ptolemy, around the globe and through a millennium. Violet Moller reveals the connections between the Islamic world and Christendom which have preserved and transformed the fields of astronomy, mathematics and medicine from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.

Uncover the top history books that encapsulate the past.