History’s greatest romances

Inspired by The Love Letters of Great Men & Women, here's our choice of the greatest (mostly doomed) love stories of all time.

History has taught us that, as Shakespeare put it, ‘the course of true love never did run smooth.' In fact a quick scroll through the greatest love affairs in history reveals that many of the lovers met a tragic end. Inspired by The Love Letters of Great Men & Women, here's our choice of the greatest (mostly doomed) love stories of all time.

Napoleon and Joséphine

Napoleon Bonaparte to Joséphine at Milan,

Sent from Verona, 13 November 1796

‘I do not love thee any more; on the contrary, I detest thee. Thou art horrid, very awkward, very stupid, a very Cinderella. Thou dost not write me at all, thou dost not love thy husband; thou knowest the pleasure that thy letters afford him, and thou dost not write him six lines of even haphazard scribble.'

Napoleon, the humble soldier from Corsica who became a great general and Emperor of France, married Josephine de Beauharnais in March 1796. She was an impoverished Creole aristocrat from the French colony of Martinique with two children from an earlier marriage.

These lines come from a letter written shortly after their wedding, when Napoleon had become commander of the French forces in Italy. In these letters,

Napoleon casts himself as the supplicant, at the mercy of his beautiful and hard-hearted wife; there is something touching and almost comical about his anxious pursuit of Josephine all over Italy while conducting the military campaign that would make his name. It became clear to both later on in their marriage that neither had remained faithful, and Josephine's extravagance was a constant source of friction between them, but it seems from these early letters that Napoleon was very much in love with his wife.

Napoleon divorced Josephine in 1810 to marry Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, in order to gain an heir and secure the succession. Josephine continued to live near Paris, and remained on good terms with her former husband until she died in 1814. After his defeat by the British, Napoleon was exiled to the island of St Helena in 1815, where he died six years later.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert

Queen Victoria to Prince Albert

Sent from Buckingham Palace, 31 January 1840

'You forget, my dearest Love, that I am the Sovereign, and that business can stop and wait for nothing. Parliament is sitting, and something occurs almost every day, for which I may be required, and it is quite impossible for me to be absent from London; therefore two or three days is already a long time to be absent. I am never easy a moment, if I am not on the spot, and see and hear what is going on.'

Victoria was the only child of Edward, Duke of Kent. Her father died in 1820, and she was brought up in near isolation at Kensington Palace. She was permitted to know of her probable destiny at the age of ten – the occasion on which, according to legend, she exclaimed, ‘I will be good!' She succeeded to the throne in 1837, when she was eighteen.

That same year Victoria was introduced to her cousin Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, a match much wished for by her mother, but the new young queen was enjoying her first taste of independence, and in no hurry to change her circumstances. It wasn't until Albert presented himself again in 1839 that she fell in love with him. Victoria, as queen, had to propose to Albert, which must have been the occasion for some awkwardness, but he accepted and they were married on 10 February 1840.

Victoria's character – headstrong, stubborn, sociable – was transformed by marriage. Albert compensated for his wife's superior status with an absolute rule in the domestic sphere, and his punishment for wifely transgressions was a withdrawal of affection. Victoria, terrified of losing the husband upon whom she was increasingly reliant, would submit, and harmony would be restored. His letters, formerly addressed to ‘Beloved Victoria', now began, ‘Dear Child'. The balance of power shifted further as the couple began to reproduce; between 1840 and 1857 Victoria gave birth to nine children, all of whom, unusually for the time, survived to adulthood.

By the 1840s, Albert was joint monarch in all but name – and the fact that he had no official title was a constant source of fretful regret to Victoria. She tried in 1854 and again in 1856 to have him declared prince consort by Parliament; when her second attempt failed, she conferred the title upon him herself.

Albert was consulted by his wife in all matters of state, and she followed his direction. It is impossible to overstate how much Victoria depended on her husband; her children were a distant second in her affections, and she would do nothing without his express approval.

When he died in 1861, probably of stomach cancer, she was utterly inconsolable, and plunged the court into a mourning so deep as to be quite spectacular even by the stringent standards of the time. She did not emerge again into the public gaze until 1872, and even then it was only at the urging of her most senior advisers, who feared that republicanism was gaining a real foothold among the populace.

The quote above is taken from a letter written to Albert ten days before their wedding. It reveals Victoria in her ‘before' state, when she feels quite at ease asserting her authority over her husband-to-be.

Empress Alexandra and Russia to Tsar Nicholas II

Empress Alexandra of Russia to Tsar Nicholas II

Sent from Tsarskoje Selo, 4 December 1916

'Good-bye, sweet Lovy! Its great pain to let you go – worse than ever after the hard times we have been living & fighting through. But God who is all love & mercy has let the things take a change for the better, – just a little more patience & deepest faith in the prayers & help of our Friend – then all will go well. I am fully convinced that great & beautiful times are coming for yr. Reign & Russia. Only keep up your spirits.'

Alexandra and Nicholas, the Tsarevich of Russia, had fallen in love against the opposition both of Alexandra's grandmother, Queen Victoria, and of Nicholas's father, the Tsar.

But with the Tsar in failing health, the objections were eventually overcome. He died on 1 November 1894; later that month, Nicholas and Alexandra were married and Alexandra became Tsarina. But life at the Russian court proved problematic. The people suspected her of being pro-German – which became an even more serious problem with the outbreak of the First World War; the nobility thought her insufficiently grand to have become empress; and her mother-in-law, the Dowager Empress, did everything she could to undermine her, including openly sneering at the fact that after ten years of marriage she had produced only daughters.

Finally, in 1904, she gave birth to Alexei, the Tsarevich. Her joy and relief must have turned to anguish when she realized that he had inherited haemophilia, an often fatal condition at the time.

In despair over the fragile health of her son, with doctors who were unable to offer any help, Alexandra turned to an array of healers, seers and mystics, the most notorious of whom was Rasputin, a kind of non-aligned monk of shady background and no credentials. Rasputin became, if possible, even more unpopular with both the people and the nobility than Alexandra herself, and was murdered by a gang of courtiers in 1916.

From some accounts of Alexandra's relationship with this charlatan, one might think she was singlehandedly responsible for the Russian Revolution. But by 1917, the country was on its knees: famine was widespread, the mismanaged war dragged on, soldiers were opening fire on protestors and the Tsar refused to contemplate any kind of constitutional reform.

After the February revolution Nicholas was forced to abdicate. He and his family were imprisoned by the Bolsheviks in various locations, and finally taken to a house at Ekaterinburg in the Urals. There, in the middle of the night of 16–17 July 1918, the entire family and three servants were taken by their guards from their sleeping quarters to the basement where, in a bloody chaos of bullets and bayonets, they were all killed.

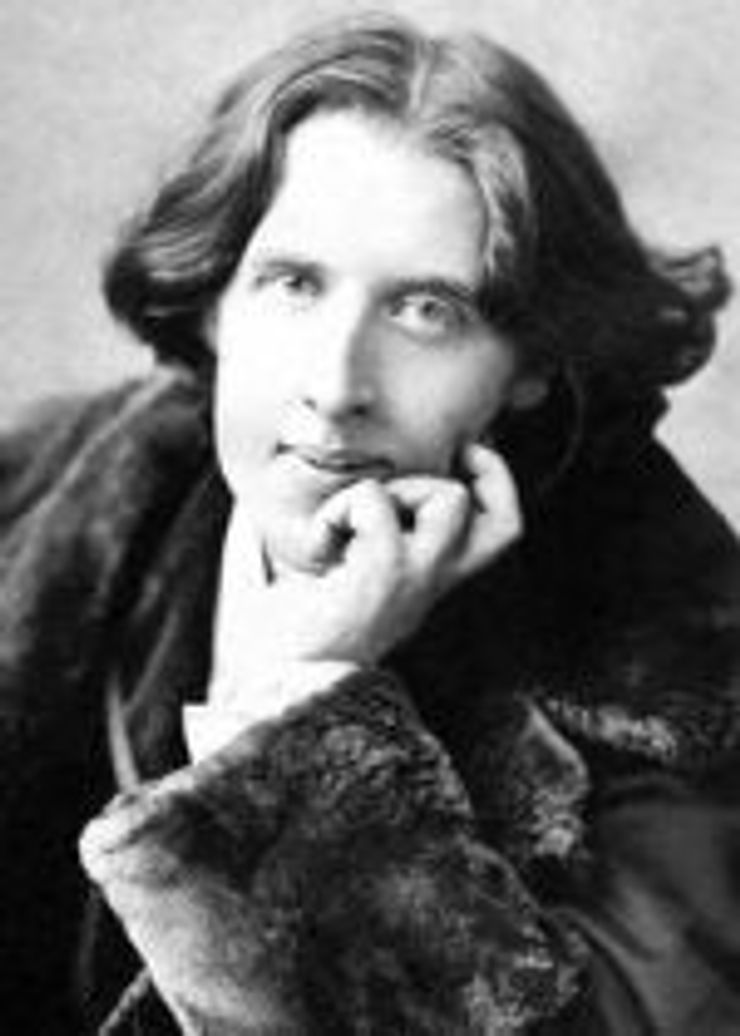

Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas

'My sweet rose, my delicate flower, my lily of lilies, it is perhaps in prison that I am going to test the power of love. I am going to see if I cannot make the bitter warders sweet by the intensity of the love I bear you. I have had moments when I thought it would be wiser to separate. Ah! moments of weakness and madness!'

Oscar Wilde was a playwright, novelist, essayist, critic, poet and wit. Wilde married Constance Mary Lloyd, a Dublin Protestant, in 1884; she gave birth to two sons in quick succession. In 1891, Wilde met Lord Alfred Douglas, son of the Marquess of Queensberry. His subsequent love affair with ‘Bosie' effectively ruined his life.

In 1895, Douglas's father, famously aggressive, infuriated by his son's relationship with Wilde, left a card at Wilde's club inscribed ‘To Oscar Wilde – posing as Somdomite [sic]'. Wilde made the unwise decision to sue for libel. The case went to court but was abandoned.

The vindictive Marquess pursued Wilde through the office of the public prosecutor, which resulted in his standing trial on various counts of gross indecency. He was found guilty and sentenced to two years' hard labour; he served his sentence at Pentonville and then at Reading.

Wilde left prison physically and psychologically destroyed. Popular belief has it that he was abandoned by Douglas, but in fact, Lord Alfred wrote letters to the newspapers protesting the sentence, and petitioned the Queen for clemency. On his release, Wilde drifted from place to place (Constance had not divorced him, but had moved away, and changed her and the childrens' surname), frequently meeting up with Douglas. He died in a Paris hotel room in 1900, declaring a few days beforehand, ‘My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has to go.'

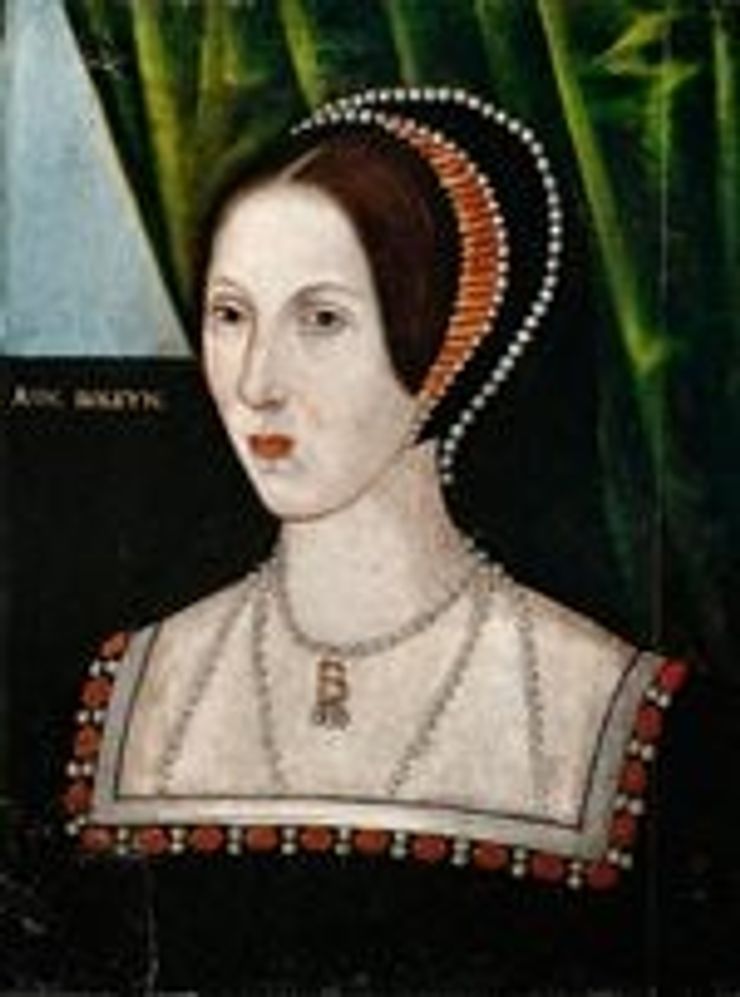

Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII

From Anne Boleyn to Henry VIII, 6 May 1536

‘You have chosen me from a low estate to be your Queen and Companion, far beyond my desert or desire, if then you found me worthy of such honour, good your grace, let not any light fancy or bad counsel of my enemies, withdraw your princely favour from me, neither let that stain, that unworthy stain of a disloyal heart towards your grace ever cast so foul a blot on your most dutiful wife and the infant princess your daughter.'

Perhaps an unlikely and unromantic choice but it's undeniable that the romance between Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn is one of the most infamous in history.

Anne Boleyn was the daughter of Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Ormond, and Elizabeth Howard. Thomas Boleyn was enormously ambitious for his three children and when at the age of thirteen Anne was offered a position as a lady-in-waiting at the court of Margaret of Austria in Brussels, he saw it as an unmissable opportunity.

Shortly after her arrival in Brussels, Anne was moved to France, where she entered the service of Claude, the queen. The two became close, and Anne acquired a polish and glamour that was immediately apparent when she returned to the English court in 1521 – accomplished, tasteful, witty and beautifully dressed, she was absolutely unlike her contemporaries.

In 1526 or thereabouts, Anne caught the eye of Henry VIII. The king was ready for a new mistress, having recently dispensed with the services of Mary, Anne's sister. But it so happened that the vacancy coincided with Henry's growing conviction, in the absence of a male heir, that his marriage to Katherine had never been valid.

The annulment of Henry and Katherine's marriage and his subsequent marriage to Anne played out over the next six years. The political and religious fallout was huge, and led ultimately to Henry's break with Rome and the establishment of the Church of England.

The couple were finally married in January 1533, when Anne was just pregnant; Princess Elizabeth was born on 7 September.

It was not a disaster for Anne that her first child was a girl; she was still young. But a miscarriage in August 1534 did not augur well, and she did not conceive again until the autumn of 1535. In January 1536, Katherine died, which came as a relief to Henry and Anne, who knew how much support she and her

daughter, Mary, retained in the country at large; this relief was short-lived, as Anne had another miscarriage at the end of the same month. Still, the situation might have been salvageable, had it not been for Anne's falling out with the Lord Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell.

Anne had to go, and Thomas Cromwell arranged it. A mere divorce would not suffice; Anne and her faction had to be permanently dispatched. So Cromwell cooked up a selection of terrible charges, accusing her not only of incestuous relations with her brother George, but adultery with four other men of her circle.All were arrested and taken to the Tower.

After trials of non-existent legality, the Archbishop of Canterbury declared Anne and Henry's marriage and void on the grounds of Henry's previous association with Mary Boleyn. On 19 May, Anne was executed on Tower Green by a swordsman brought over from France in order to spare her the axe. On 30 May Henry married Jane Seymour, one of Anne's ladies-in-waiting.

Love Letters of Great Men and Women

by Ursula Doyle (Ed.)

From the private papers of Jane Austen and Mozart to those of Anne Boleyn and Nelson, Love Letters of Great Men and Women collects together some of the most romantic letters in history.

Fall in love with the best romance novels of all time.