Ken Follett on A Column of Fire

Ken Follett talks about the inspiration behind his third Kingsbridge novel, A Column of Fire.

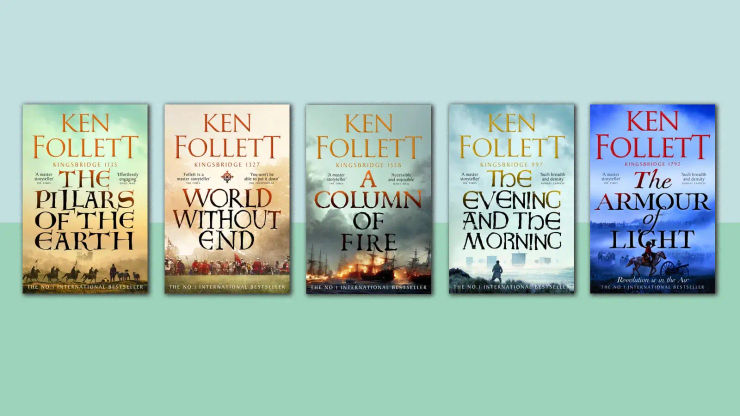

A Column of Fire, is a historical novel about spies and secret agents in the sixteenth century, the time of Queen Elizabeth I. Set partly in the fictional town of Kingsbridge, it is a sequel to The Pillars of the Earth and World Without End. Here, Ken Follett talks about how real historical events inspired A Column of Fire.

Were you excited about returning to Kingsbridge?

You bet. We've watched the place grow from an Anglo-Norman settlement to a thriving medieval town, and now we see it at the start of the English Renaissance. Kingsbridge is England in miniature.

Where did the idea for A Column of Fire come from?

I read somewhere that Queen Elizabeth I started the first English secret service. That intrigued me, and I read several books about spies and secret agents in the sixteenth century. I felt sure this could be the basis of an exciting novel.

Why did you choose to call the book A Column of Fire?

It's biblical, like The Pillars of the Earth. Spies are sometimes referred to as a Fifth Column. And a lot of people were burned at the stake in the sixteenth century.

We know that A Column of Fire is about spies and secret agents in the sixteenth century, what are the other themes surrounding the book?

Most of my recent books are about people struggling for freedom in one form or another: Welsh coal miners, Russian factory workers, Jews, African Americans. This is about religious freedom.

How do these themes relate to your own life?

I've always hated people who assume they have authority over me. This made my schooldays a challenge, obviously. A bully makes me angry. I empathize with fictional characters who fight against tyranny.

What sort of research did you do for A Column of Fire?

There's nobody left to interview, of course. As usual, most of my information comes from history books. I also visited houses and castles built in this period. I looked at sixteenth century clothing in the London Museum, and I went several times to the National Portrait Gallery to study the faces of Queen Elizabeth, Mary Queen of Scots, Francis Drake and many others.

Did you visit the locations of the key events in A Column of Fire?

Scotland for Loch Leven, the prison from which Mary Queen of Scots escaped; Belgium for Antwerp, then the banking centre of the western world; Spain for Seville, the richest city in Spain; Paris because it was the headquarters of those who conspired to assassinate Queen Elizabeth.

Plenty of historians have written about this era. Who among them do you particularly like or respect?

Robert Hutchinson has written well about espionage at this time. Geoffrey Parker is the authority on the long and bloody war in the Netherlands. Perhaps the most useful book was Conyers Read's three-volume biography Mr Secretary Walsingham, about the man who was the Elizabethan equivalent of “M” in the James Bond stories.

Are any of your fictional characters based on real people?

Not really. I might give a villain the hair style of someone I dislike, and of course the female heroes all have something in them of Barbara, my wife; but my fictional characters are never portraits of real people.

A Column of Fire has a number of real historical characters, including several heads of state. Who did you particularly admire?

Three great sixteenth century leaders understood the need for religious tolerance, and interestingly they were all women: our Queen Elizabeth I; Caterina dei Medici, who was queen of France and then Queen Mother; and Marguerite de Parme, governor of the Netherlands. In an age of relentless bigotry, each of them tried to persuade people of rival religions to live in peace. For that they were hated. Their efforts were only partly successful. Each of them was undermined: Elizabeth by repeated plots to assassinate her, Caterina by the ruthless Guise family, and Marguerite by her half-brother King Felipe II of Spain. I admire their idealism, courage and persistence in the face of bloodthirsty opposition.

What are you most proud of in your career?

It was a pretty good achievement to write a novel about the rather unpromising subject of building a cathedral in the Middle Ages and turning it into an international No.1. We've sold about twenty-six-million copies of The Pillars of the Earth. That's pretty good for a book a lot of people thought would be too dull.

How long did it take you to write?

The whole thing took three years and three months. After two years I only had about 200 pages, and I felt this was a crisis. And as a novelist the only thing you can do if you want to write faster is work more hours. So I started to work Saturdays and then Sundays as well. The difficulty is simply that you've got to keep on making up more and more stuff about the same people. If you write 100,000 words of a thriller, then it's finished. But after 100,000 words of The Pillars of the Earth that's only a quarter of the book. I still had three-quarters to go and that was the great difficulty.

Some writers live in dread of their books being turned into films or TV series. Have you enjoyed the experience?

Seeing good actors giving good performances, bringing to life characters I've invented and speaking some of the lines I've written is a huge thrill. When it all goes well it's great. When it goes badly you cringe when you see what's on the screen, but you have to take that risk. I'm pleased and proud that some of my stories have made good film and TV. It confirms the strength of the story that it can be transformed from one medium to another. And I'm also pleased that my stories have been turned into a stage musical, several board games, and a computer game.

What's next?

I'm working on a new story, but I'm not yet ready to talk about it—sorry!

A Column of Fire

by Ken Follett

Christmas 1558, and young Ned Willard returns home to Kingsbridge to find his world has changed. The ancient stones of Kingsbridge Cathedral look down on a city torn by religious hatred. Europe is in turmoil as high principles clash bloodily with friendship, loyalty and love, and Ned soon finds himself on the opposite side from the girl he longs to marry, Margery Fitzgerald.

Then Elizabeth Tudor becomes queen and all of Europe turns against England.

Over a turbulent half-century, the love between Ned and Margery seems doomed, as extremism sparks violence from Edinburgh to Geneva. With Elizabeth clinging precariously to her throne and her principles, protected by a small, dedicated group of resourceful spies and courageous secret agents, it becomes clear that the real enemies – then as now – are not the rival religions.

Photo © Olivier Favre