Behind the scenes at the Coronation: 'as every monarch knows, nodding while wearing a crown is extremely risky'

Royal biographer Robert Hardman takes us to the 'rehearsal studio' at Buckingham Palace where the new King and Queen prepared for the ceremony.

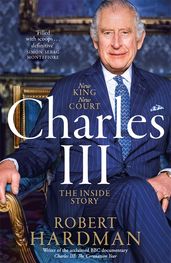

Charles III, by the acclaimed royal biographer and author of Queen of Our Times, Robert Hardman, is a brilliant account of a tumultuous period in British history, full of intriguing insider detail. In this edited extract, we go behind the scenes at rehearsals for the Coronation.

At last, the moment has come. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, stands solemnly before the King, arms aloft, preparing for the climactic moment when St Edward’s Crown is placed on the royal head. His hands start to descend. At which point, the King offers some practical advice: ‘You have to jam it on.’ He points a gloved hand to his eyebrows. ‘It has to come down to here first – and then push down. Because otherwise, if it’s at the back, it’s fatal.’ The Archbishop explains that he is worried about hurting his monarch. ‘I don’t want to break your neck, sir. It might ruin the service!’ The King gives him a reassuring smile. ‘It won’t,’ he assures Welby. ‘But it’s so huge. It’s got to be on right and I can’t do anything about it.’ The last thing anyone wants is a wobbly crown.

There is, in fact, no crown at this point. It is 21 April 2023 – nine days before the Coronation. This is yet another rehearsal and the Archbishop is doing his best to improvise, with an invisible crown between his hands. He duly follows the advice of the King and gives the imaginary five-pound circlet of bejewelled gold and velvet a good shove. Here is another instance of the gently shifting balance between 1953 and 2023. Seventy years ago, a young Queen was deferring to an elderly archbishop four decades her senior. Now, the oldest candidate for crowning in British history is giving a few tips to an archbishop who, unlike himself, has never seen a coronation before. Welby is more than happy to take lessons. As he explains afterwards, there is really only one way to ensure a faultless ceremony: ‘Repetition, repetition, repetition.’

‘Seventy years ago, a young Queen was deferring to an elderly archbishop four decades her senior. Now, the oldest candidate for crowning in British history is giving a few tips to an archbishop who, unlike himself, has never seen a coronation before.’

For the final few weeks before the ceremony, the ballroom of Buckingham Palace has been transformed into a rehearsal studio. It now houses a full-scale replica of the business end of Westminster Abbey, otherwise known as the Coronation ‘theatre’. Not only is there a temporary raised floor, just as there will be in the abbey, but the Royal Household workers have installed identical blue and gold carpet. Even the throne itself appears identical to the one in the abbey. On closer inspection, it is not actually the very ancient St Edward’s Chair but its twin. When the abbey held the joint coronation of William and Mary in April 1689, they built a second throne for Mary and this is it. The only obvious difference is that it does not have a space for the Scottish Stone of Destiny built in beneath the seat. So, Mary’s Chair will serve as the throne during these rehearsals. Day after day in the lead-up to the Coronation, different players have been in here going through their parts, with various stand-ins. They include the first female bishops in history to participate in a coronation, Rose Hudson- Wilkin of Dover and Guli Francis-Dehqani of Chelmsford. With ten days to go, they will be joined by the King and Queen Consort. Earlier this afternoon, the King’s valet, Lee Dobson, was here standing in for his boss and wearing a replica of the colobium sindonis and the other vestments. That way, the Bishops of Durham and of Bath and Wells could practise getting the King in and out of his various chairs without twisting his robes. By the time the King and Queen arrive for this rehearsal, two dozen people are going through their paces. The appearance of the royal couple causes a brief stiffening, but it is clear the pair are more relaxed than anyone else. The mood actually lightens. The King produces a pair of glasses to read his draft order of service and reminds his team that he needs cue cards with large lettering on the day. (An autocue monitor is out of the question.) The King can’t be fiddling with spectacles when he is trying to grasp his sceptres and orb. ‘There is one moment where he has to try to hold three things in two hands,’ the Archbishop recalls later. ‘I said that was a bit Monty Python and he roared with laughter.’ With so many carefully choreographed movements, Justin Welby likens the whole exercise to a musical. ‘You really are moving in rhythmic and detailed ways,’ he explains.

‘Having a clergyman who is neither a hairdresser nor a milliner placing a heavy crown on one’s immaculate hairstyle is challenging enough. Having oil smeared on one’s face is of rather greater concern.’

Others find themselves transported back to the days of the school play. After all, Justin Welby keeps talking about ‘the cast’, coronations take place in the ‘theatre’ of the abbey and the King was a keen actor in his youth. ‘We often remark upon how grateful we are that our schools did a lot of drama and both of us spent time on stage,’ the Princess Royal reflects. ‘It’s really good training. Apart from the fact it gives you a bit of confidence, it teaches you about learning lines and making sure you do the rehearsals so you get it absolutely right.’

For Queen Camilla, all along, the main anxiety has been the anointing. Just like monarchs, queen consorts are also anointed at coronations, though to a lesser extent. Having a clergyman who is neither a hairdresser nor a milliner placing a heavy crown on one’s immaculate hairstyle is challenging enough. Having oil smeared on one’s face is of rather greater concern. ‘Just a tiny bit of oil, I promise,’ the Dean of Westminster, Dr David Hoyle, assures her. ‘It is the merest dab,’ the Archbishop insists, as he imitates the short sign of the cross he will make on her forehead.

For the King, the anointing of the Queen is a slightly nerve-wracking moment, too. Before she is crowned, the Archbishop has to seek the affirmation of the monarch who must ‘nod’ his approval from the Throne Chair. Except, as every monarch knows, nodding while wearing a crown is extremely risky. For, if you lower your head, the whole thing can topple forwards and fall off. That would be a disastrous portent at the start of a reign. It is why the late Queen always asked for the Imperial State Crown to be delivered the day before the State Opening of Parliament. That way, she could wear it around the house and get used to it. When reading the Queen’s speech, as she revealed to the broadcaster Alastair Bruce, she would always hold the words up to her face. Lowering one’s gaze was much too dangerous. ‘If you did, your neck would break,’ she explained. The Archbishop is sympathetic and also aware of the dangers of asking the King to bow his head with five pounds of gold perched on top of it. He has a solution: ‘Just give me a look that says you mean it!’

Read more in the Sunday Times number one bestseller:

Charles III

In Charles III royal biographer Robert Hardman has chronicled the extraordinary first year of the new monarch’s reign. Offering up fresh insight into Charles III’s and Queen Camilla’s partnership, his much-reported relationships with his sons, and how he managed his grief for the death of his mother with his desire to show his strength to the British people, Charles III is an authoritative examination of a tumultuous year for the Royal Family, and the man at the heart of it all.