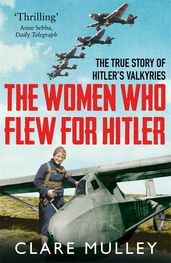

Synopsis

A riveting double biography of Nazi Germany's most highly decorated women test pilots – Hitler's personal Valkyries.

Hanna Reitsch and Melitta von Stauffenberg were talented, courageous and strikingly attractive women who fought convention to make their names in the male-dominated field of flight in 1930s Germany. With the war, both became pioneering test pilots and both were awarded the Iron Cross for service to the Third Reich. But they could not have been more different and neither woman had a good word to say for the other.

Hanna was middle-class, vivacious and distinctly Aryan, while the darker, more self-effacing Melitta, came from an aristocratic Prussian family. Both were driven by deeply held convictions about honour and patriotism but ultimately while Hanna tried to save Hitler's life, begging him to let her fly him to safety in April 1945, Melitta covertly supported the most famous attempt to assassinate the Führer. Their interwoven lives provide a vivid insight into Nazi Germany and its attitudes to women, class and race.

Acclaimed biographer Clare Mulley gets under the skin of these two distinctive and unconventional women, giving a full – and as yet largely unknown – account of their contrasting yet strangely parallel lives, against a changing backdrop of the 1936 Olympics, the Eastern Front, the Berlin Air Club, and Hitler's bunker. Told with great narrative flair, The Women Who Flew for Hitler is an extraordinary true story, with all the excitement and colour of the best fiction.

Details

Reviews

Vividly drawn . . . this is a thrilling story.

This is popular history of a high order.

A satisfying, rollicking read . . . well researched and beautifully written.

This compelling work has the drama and suspense of the best movie scripts.