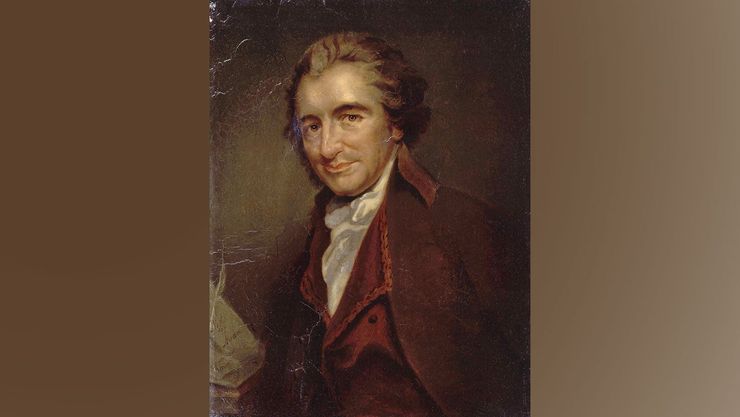

Who was Thomas Paine?

Learn more about the British radical writer, Thomas Paine.

'Neither farmer, manufacturer, mechanic, merchant nor shopkeeper... I am a Farmer of thoughts' - Thomas Paine

We take a closer look at who the radical writer Thomas Paine really was.

1. New World, New Name

Thomas Paine was born in Thetford in Norfolk in 1737, the son of a Quaker stay maker. The ‘e' at the end of his surname came and went but in keeping with countless transatlantic reinventions, only became a permanent fixture after his arrival in America in 1774.

Having followed his father into stay making, Paine had spent time at sea as a privateer, knocked around in Kent and London, where he befriended Benjamin Franklin, and worked as a tax collector before he was dismissed for irregulars over his books. Subsequently hired as an exciseman in Lewes, Sussex, he joined the local writing and debating club, but was again sacked, this time for petitioning the government for higher pay and attempting to unionise the workforce. His first wife and their baby had died in childbirth, and a second marriage to the daughter of a Quaker tobacconist in Lewes ended in separation when the business they'd inherited went bankrupt. With little else to lose, Paine opted to use a £35 settlement from his wife to sail to Philadelphia, having secured a letter of introduction to a few of its more notable inhabitants from Franklin. On the eight-week voyage, he came down with typhus, and landing on 30 November 1774, was too sick to walk and had to be carried ashore.

2. A Share in Two Revolutions

Paine had the distinction of participating in two revolutions: the American War of Independence and the French Revolution. The former broke out at the end of 1775,largely in response to the imposition of new taxes and surplus goods, especially tea from the East India Company, on the colonies by the British government. The mother country had been seeking to replenish its coffers after the expense of the Seven Years War – a conflict that had seen it gain control of several former French territories in North America and the West Indies.

Paine was the right man in the right place, as the first Continental Congress, a gathering of the thirteen American colonies to form a response to the so-called Intolerable Acts of King George III, had been convened in Philadelphia only a few months before his arrival there. If rebellious talk was rife in the city of brotherly love, Paine was still one of the earliest writers to put the case for full American independence from Britain, driving the point home most persuasively in a pamphlet published on 10 January 1776 and entitled Common Sense.

According to Mark Philp, Common Sense was ‘the most widely distributed pamphlet of the American War of Independence and has the strongest claim to have made independence seem both desirable and attainable to the wavering colonists.' Paine made it a matter of principle to not accept money from his political and religious writings and signed the royalties from Common Sense over to the Continental Army, where the money helped buy mittens for patriots fighting the British in Quebec. Paine himself enlisted in the Continental Army and acted as an aide-de-camp to Nathaniel Greene, one of Washington's generals, but mostly served the cause as a non-combatant, supporting the revolution by writing numerous rallying pieces and tracts.

Just over a decade later and back in Britain, Paine's pen would run to support the similarly anti-monarchist French Revolution when in March 1791 he published the first part of his most famous work, Rights of Man – a book that Napoleon Bonaparte once claimed to keep a copy of under his pillow. It was written as a rebuttal to his one-time friend Edmund Burke, who had denounced the revolutionary movement after the storming of Bastille in July 1789 in a series of speeches in the Houses of Parliament, which were subsequently published as Reflections on the Revolution in France.

Leaving Britain in September 1792, under the threat of arrest for sedition, Paine arrived in Calais to a hero's welcome and was made an honorary French citizen, and elected to the French National Convention. But after speaking out against the execution of Louis XVI, he fell out with Robespierre's administration and only narrowly avoided the guillotine himself. Paine languished in the Luxembourg Prison in Paris for close to a year before being freed after Robespierre's own fall from power in 1794.

3. Godfather of America's First National Bank

Paine's personal finances were always a disaster: upon returning to America in 1802 he was almost immediately arrested on a charge of ‘indebtedness'. But in 1780, at the height of the revolution and with the Continental army lacking funds, Paine had written a piece urging the wealthier merchants and traders of Philadelphia to form a subscription society to raise money for essential military supplies and equipment. The direct result was the establishment of the Revolutionary Subscription Bank. The cash it collected served as the foundation for the first bank in the United States, the Bank of Pennsylvania, later charted by congress as the national Bank of North America and the forerunner of the Federal Reserve.

4. Paine's Iron Bridge

Following the successful conclusion of the American Revolution, Paine had originally intended to retire from politics and pamphleteering. In 1783, he withdraw to a small farm at Bordentown, New Jersey, where his stated ambition was to spend the rest of his years toiling in 'the quiet field of science'. And it was during this period that he drew up plans for a radically new type of iron bridge with a single 400-ft span that he believed could be suitable for Philadelphia's Schuylkill River. While bridge building might seem far removed from the inky world of journalism or bloody revolutions, Paine's scheme for an iron span was in many respects driven by the same Enlightenment principles and a faith in scientific, as well as political, progress.

A model of Paine's bridge was eventually put on display at the State House in Boston in December 1786. But failing to find sufficient backers in America, he travelled to Europe and presented his design to the French Academy of Science in Paris and the Royal Society in London. In September 1788, he took out a patent for ‘A method of constructing of arches… on principles new and different to anything hitherto practised' and visited Walkers of Rotherham, at that time one of the leading iron foundries in country, and managed to persuade them to build him two prototypes of the bridge – one of which he hoped to erect over the River Thames.

Sadly, it only ever got as far the show ground of Yorkshire Stingo pub in Lisson Grove, Paddington. Here in May 1790, punters were charged a shilling a go to marvel at Paine's own small, but destined never to be realised, contribution to the still nascent Industrial Revolution.

5. A Dirty Drunk

That his iron bridge got no further than a pub is rather fitting. As it happens, most of Rights of Man would be written in another London hostelry, the Red Lion Inn in Islington. But Paine was also famously rather fond of a tipple. Nearly all of his articles were penned with a decanter of brandy to hand and at least three glasses were said to be required for most pieces. In times of stress, of which there was no shortage in his eventful life, and even given the levels of alcohol consumption of those gin-soaked times, Paine certainly drank to excess. He was also extremely careless about his appearance, washing so little and infrequently, that once hosts in France forced him to take a bath.

6. The Filthy Atheist

In the latter part of his own lifetime and for close to a century after his death Paine's reputation came under severe attack, with Theodore Roosevelt in 1888 dismissing him ‘a filthy little atheist'. It was a common enough view of Paine by then, and largely based on the notoriety of one his most audacious books, The Age of Reason.

A critique of the Bible and the tyranny of organised religion, it had been composed in Paris in around 1793 and was first published there with the aim, or so Paine later told Samuel Adams, of preventing the French from ‘running headlong into atheism.' Although also stating in the book that he believed in ‘one God, and no more' and hoped ‘for happiness beyond this life', it nevertheless, became known throughout the English-speaking world as ‘the Bible of Atheism', and was dubbed ‘a pamphlet against Jesus' by one critic. In Britain booksellers were prosecuted for selling it. Despite this, it sold in vast quantities, but ostracised Paine from many of his former friends and revolutionary colleagues and even the neighbours at his farm in New Rochelle, New York.

7. Missing Bones

Thomas Paine died age 72, in a rooming house in Greenwich Village on 8 June 1809, and was buried with little ceremony at in a plot at New Rochelle. Only six people attended his funeral - one of whom, by all accounts, was the coffin maker seeking payment.

In 1819, William Cobbett, the Tory turned agrarian radical, was seized by the idea of bringing Paine's body back to England. Cobbett argued that it was unjust he lay ‘unnoticed… in a little hole under the grass and weeds of an obscure farm in America'. That autumn, he and his son travelled to New Rochelle and, without permission, dug up Paine's coffin and, having spirited it back to New York, succeeded in getting it aboard a ship bound for Liverpool.

What happened next is a matter of immense dispute. The most romantic version of events has Paine's coffin being swept into the Atlantic ocean during a storm on the voyage back. This impromptu burial at sea, placing his bones, pointedly, midway between the land of his birth and the county he helped found. Less savoury tales have his bones being exhibited or sold off, or stolen, and then turned into trinkets and lost after Cobbett's death. In any case, today their whereabouts remain unknown.

7. A War Memorial

In 1943, an American B-17 flying fortress bomber stationed near Paine's birth of Thetford was named in Paine's honour and Units of the US Eighth Airforce placed a plaque in front of Thetford's town hall bearing the inscription: ‘This simple son of England lives on through the ideal and principles of the democratic world for which we fight today.'

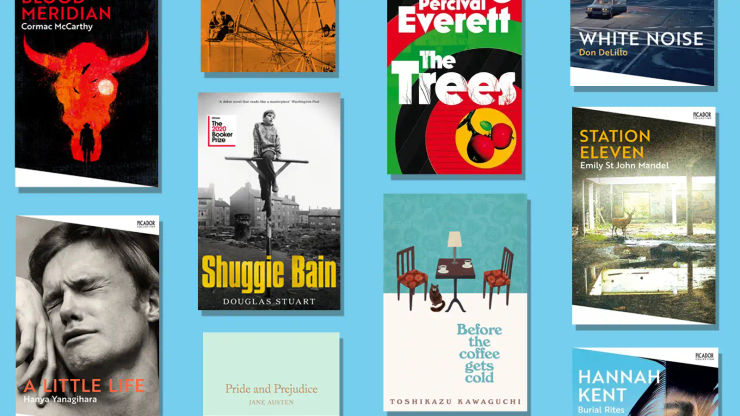

Travel through the past with more historical fiction and the best history books.