History

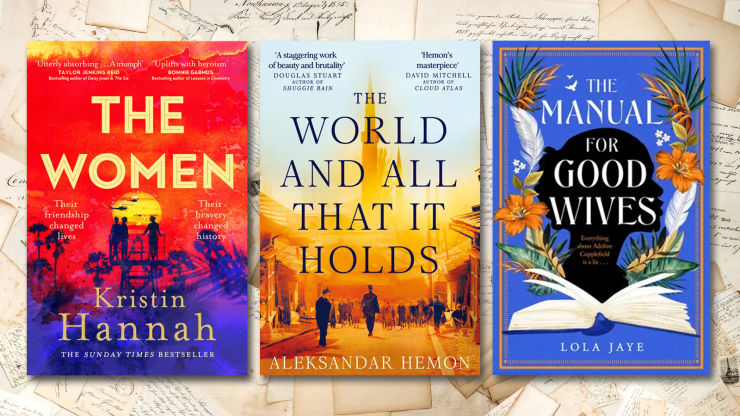

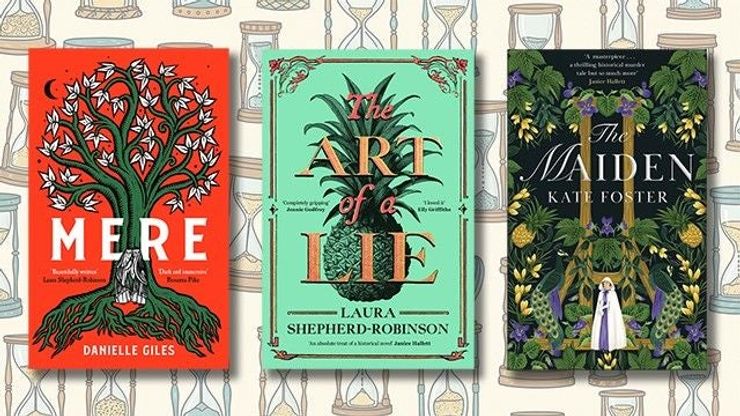

The 50 best historical fiction books of all time

The 50 best history books of all time

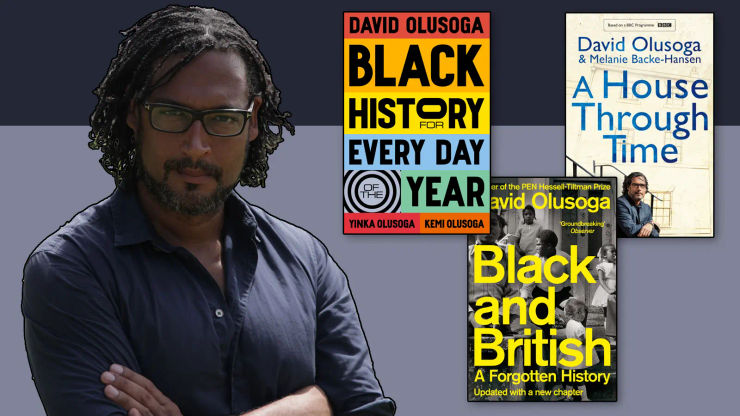

David Olusoga's books: a complete guide

Eight novels that will transport you through Britain's past

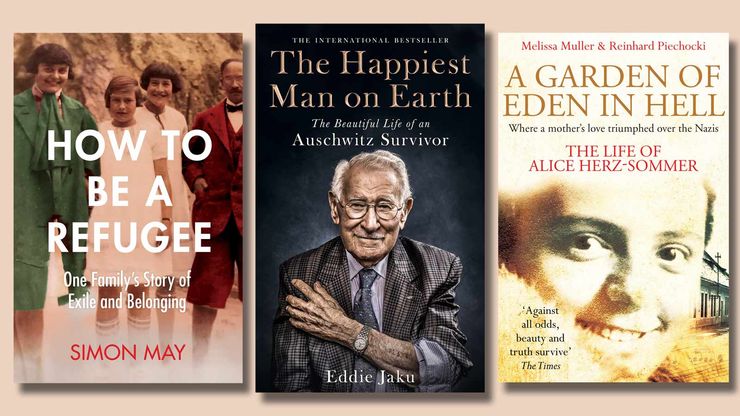

Eighteen essential books about the Holocaust

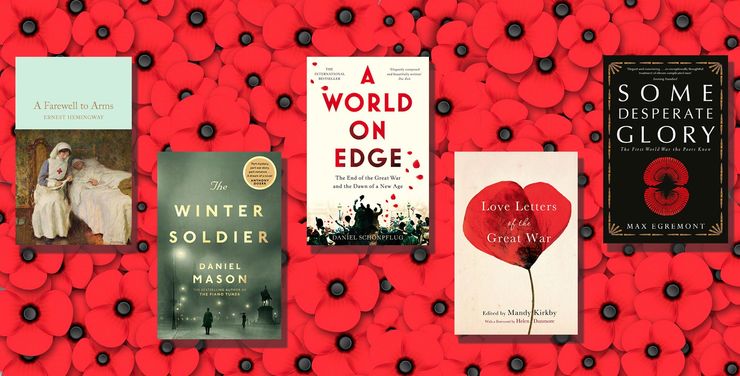

The best books about the First World War

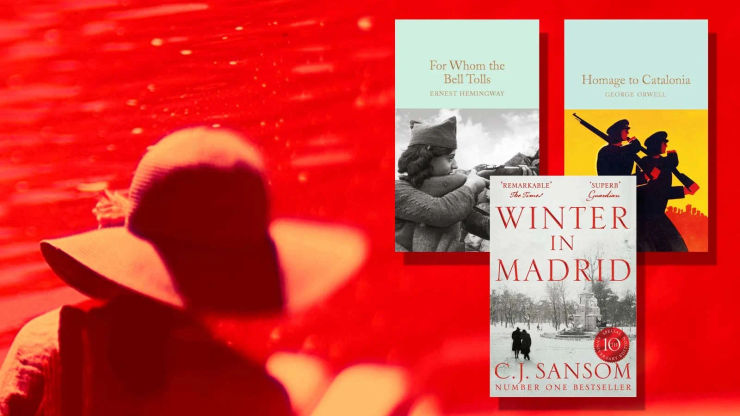

The best books about the Spanish Civil War

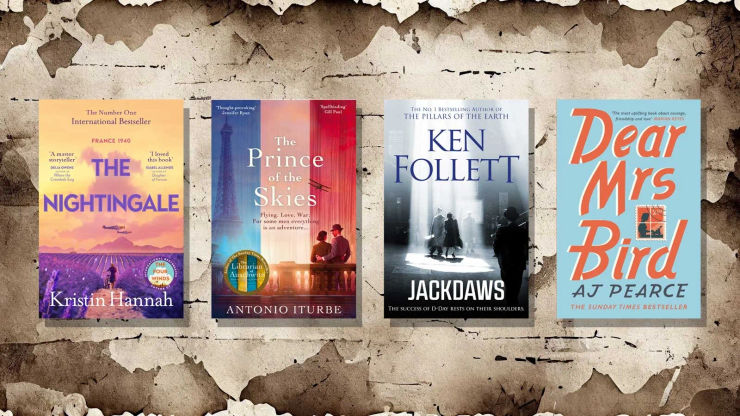

The best novels set in World War Two

Black history for every day of the year: well known figures and unsung heroes

A history of the invisible: exploring the overlooked details of everyday life

3 lessons I learnt from Eddie Jaku, survivor of Auschwitz

Kate Mosse on five warrior queens you may not know about