The Untold History of the Spitalfields Silk Weavers

Liz Trenow, author of The Silk Weaver, describes how her family history inspired her new historical romance set in the dangerous world of London's silk trade.

Liz Trenow, author of The Silk Weaver, describes how discovering the house in which her silk weaving ancestors lived and worked in nearly three hundred years ago led to the inspiration for her new historical romance.

I was born into a family of silk weavers whose business started in the early 1700s in Spitalfields, East London and are one of just three companies still weaving today (now in Sudbury, Suffolk).

No-one had ever written a history of the company – surely one of the oldest family-owned businesses in the country – so that's what I set out to do. Although we can trace an ancestor back to 1666 (a very inauspicious year), the first recorded address I discovered was in Wilkes Street, then called Wood street. Wonderfully, the house is still there.

Just a few yards away, on the corner of Wilkes Street and Princelet Street, then called Princes Street, is the house where the eminent silk designer, Anna Maria Garthwaite, lived from 1728 until her death in 1763. It was here, at the very heart of the silk industry, that she produced over a thousand patterns for damasks and brocades, many of which are today in the Victoria and Albert Museum. I became fascinated by the idea that my ancestors would have known, and possibly worked with, the most celebrated textile designer of the eighteenth century, whose silks were sought after by the nobility in Britain and America.

She was noted for her naturalistic, botanically accurate designs and credited in the Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce of 1751 as one who ‘introduced the principles of painting into the loom'. She lived in the age of enlightenment when scientists and artists were obsessed with exploring and recording the Natural World, and when botanical illustrators such as Georg Ehret became minor celebrities.

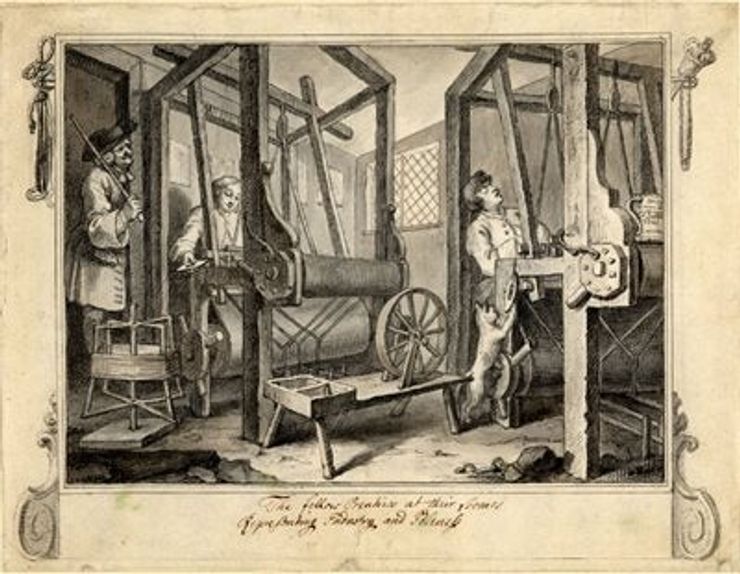

In an unpublished manuscript in the National Art Library, unfinished at her death, the late Natalie Rothstein, formerly curator of textiles at the V&A, hints at a tantalising connection between the artist William Hogarth and the weavers of Spitalfields: One of his famous series of prints, Industry and Idleness, published in 1747, shows weavers at their looms. six years later he published An Analysis of Beauty, in which he proposed that the serpentine curve – as seen in nature and the human form – was the essence of visual perfection. Is it possible, Ms Rothstein suggests, that he could had been inspired by Anna Maria's designs?

Yet no-one, not even Natalie Rothstein, has been able conclusively to discover how Anna Maria, who showed a youthful artistic talent, learned the highly technical and complex skills of designing for silk. Or how a single woman by then in her middle years managed to develop and conduct such a successful business on her own account in what was a largely male-dominated industry. It is this mystery that sparked the idea for the novel. And, my goodness, I so enjoyed the research, getting myself fully immersed into that fascinating era.

It is said that at that time a quarter of all those living in Spitalfields and Bethnal Green spoke only French – they had their own institutions including a French church, which has since been a synagogue and is now a mosque. Although, as protestants, the Huguenots were officially welcomed in England, there is much evidence that these refugees were subject to racism and mistrust, much as refugees fleeing persecution in their own lands are today.

Of course as a novelist you can also play fast and loose with history. In The Silk Weaver, I have taken enormous liberties, in particular the timing of events. Anna Maria hailed from Leicestershire, not Suffolk, and did not come to London until she was 40. Her fame was at its height in the 1730s and 40s and she died in 1763 at the good old age of 75.

Although there were always rumblings of discontent among weavers, the ‘cutters riots', and most notably the trial and hanging of two men called D'oyle and Valline, did not take place until the 1760s, around the time of Anna Maria's death. It is in this period of extreme industrial unrest that I have chosen to set the novel, even though Anna Maria probably witnessed little of it.

But just to prove I do know the difference between fact and fiction, I've included in the book a timeline of the events that inspired me, and some of the books and websites that have helped me build a picture of life in Spitalfields at that time.

I really hope you enjoy reading the book as much as I enjoyed writing it!

The Silk Weaver

by Liz Trenow

1760, Spitalfields. Anna Butterfield’s life is about to change forever, as she moves from her idyllic Suffolk home to be introduced into London society. A chance encounter with a French silk weaver, Henri, draws her in to the volatile world of the city’s burgeoning silk trade.

As their lives become ever more intertwined, Henri realises that Anna’s designs could give them both an opportunity for freedom. But his world becomes more dangerous by the day, as riots threaten to tear them apart forever . . .