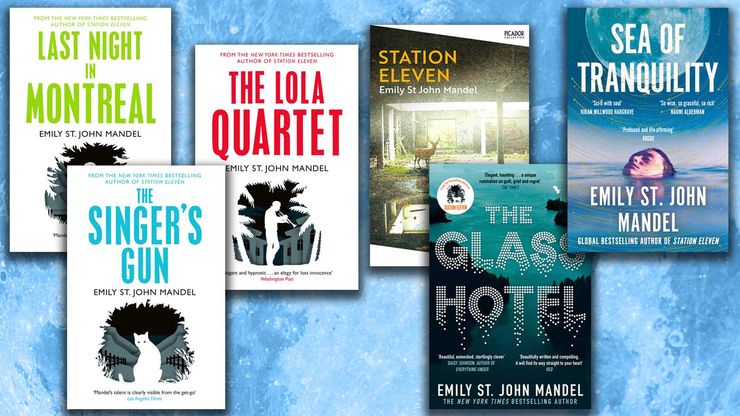

A guide to Emily St. John Mandel's books in order

From north American noir to time travel and parallel existences, Emily St. John Mandel's writing is impossible to categorise. Learn where to start reading with our guide to her work.

You can't pin a genre on Emily St. John Mandel. What you can be certain of, though, is the virtuosity of her writing. The bestselling author of six novels, her breakout success was Station Eleven, which was followed by The Glass Hotel, selected by President Barack Obama as one of his favourite books of 2020, and her most recent, Sea of Tranquility. All very different, they can be enjoyed as standalone novels, and are also in brilliant, intriguing conversation with each other. Here you will find prose as precise and clear as glass, intricate, meticulous plotting, and an underlying feeling of otherworldliness, with characters living strange, twilight lives. Take a look at our guide to Emily St. John Mandel's books in order to help you decide where to start – or continue!

Do I need to read Emily St. John Mandel's books in a particular order?

In short, no – but some readers may prefer to (more on this below). Just go with what you enjoy reading. If you like dystopia, start with Station Eleven. If you like time travel and science fiction, try Sea of Tranquility. If you prefer crime or noirs, take a look at her earlier novels, like Last Night in Montreal.

Are Emily St. John Mandel's novels connected?

Emily St. John Mandel's most recent three books, Station Eleven, The Glass Hotel and Sea of Tranquility, are connected. If you're a reader who loves finding interconnections and literary Easter eggs, you may want to read at least these three in order of publication, but they are just as enjoyable taken as standalone novels.

There are, in fact, threads running through all six of her books (look out for fedoras!). Mandel is clearly interested in the idea of parallel existences and it could be argued that all of her books can be read as parallel strands of each other. Either way, once you've started, you're unlikely to stop at just one.

Emily St. John Mandel's books in order

Last Night in Montreal

by Emily St John Mandel

Emily St. Mandel's debut is a gripping piece of crime fiction: a depiction of a life on the run; a portrait of a woman who lives only in the present tense. Unable to remember her life before being taken (apparently willingly) from her mother under cover of darkness, and constantly on the road, Lilia is never more than a few weeks away from her last night somewhere. But then she meets Eli, who's not ready to let her go without a fight. And he isn't the only one following her. The twin mysteries – why Lilia left, and why an obsessive PI who finds her, continues to follow, long after his official pursuit is over – make this a gripping, haunting book, the writing akin to the air just before it snows, the final chapters in Montreal a dark, brittle, navy.

The Singer's Gun

by Emily St John Mandel

The opening events of Emily St. John Mandel's second novel have a surreal, almost Kafkaesque quality. As Anton Waker prepares to marry his fiancé for the third time, he is suddenly moved from a managerial position in a New York consultancy to an isolated office on an otherwise uninhabited mezzanine level, where he has no work to do and is ignored by IT support. As Anton's backstory, and that of his secretary, Elena, tantalizingly drip through the present-day narrative, a story of people trafficking, blackmail and fugatives, of all kinds, gradually reveals itself.

The Lola Quartet

by Emily St John Mandel

As high school comes to an end, The Lola Quartet (Jack, Daniel, Sasha and Gavin) play one last concert. During the final song, Gavin's girlfriend Anna delivers a message via paper aeroplane – I'm sorry – and disappears. Ten years later, Gavin sees a photograph of a little girl who looks uncannily like him and who shares Anna's surname, and everything starts to come loose. As Gavin tries to track the girl down, a frightening story of teenage mistakes, fragile memories and a stolen $121,000 begins to emerge.

Station Eleven

by Emily St John Mandel

One snowy night in Toronto famous actor Arthur Leander dies on stage while performing the role of a lifetime. That same evening a deadly virus touches down in North America, and the world is never the same again. The carefully plotted time-slip narrative moves between the years before, during and after a virus kills 99.9% of the world's population. Twenty years after the almost complete collapse of civilisation, a group of musicians and actors called The Travelling Symphony journey across an almost-deserted United States, bringing a little light to the settlements that have grown up since. But then they start to hear stories about a mysterious, and dangerous, Prophet. Already a critical and commercial success, Station Eleven gained thousands of new readers in 2020 thanks to its eerily prescient post-pandemic dystopian setting.

Don't Miss

'Believe it or not, the pandemic was entirely incidental to the plot.' Emily St. John Mandel on Station Eleven

Read moreThe Glass Hotel

by Emily St John Mandel

‘Why don’t you swallow broken glass.’ A hooded figure scrapes a provocative note into a window. A New York financier hands a beautiful bartender his card. A Ponzi scheme collapses, and a woman disappears from the deck of a container ship. Fans will enjoy spotting the connections and allusions to the events of Mandel's previous novel, but this is a parallel universe of Station Eleven rather than a sequel. It's an elegant exploration of guilt, grief and regret, Mandel's crystal prose shining like the glass hotel out of the darkness.

Sea of Tranquility

by Emily St John Mandel

It is perhaps not surprising that a novelist who is so expert with time-slip narratives would come to write an out-and-out time travel book and Sea of Tranquility is the most overtly science-fiction of Mandel's novels. An exiled Englishman in the early twentieth century, a writer trapped far from home in the future and a girl destined to die too young in the present day, each glimpse a world that is not their own, and a time-traveler is sent back from the 2400s to investigate. Sea of Tranquility is much more explicitly linked to the world(s) of The Glass Hotel and Station Eleven than those novels are to each other, and acts as a kind of meta-fictional response to the latter – the book's cast of characters include a writer famous for a pandemic novel, caught up in a pandemic.