An interview with Ken Follett

The bestselling author on genre-hopping, James Bond and why he keeps returning to Kingsbridge.

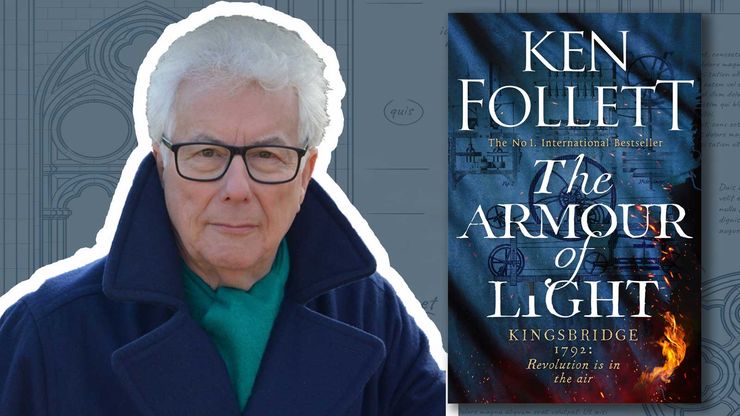

The Armour of Light, Ken Follett’s fifth novel set in the fictional town of Kingsbridge, takes us to the late eighteenth century. Revolution is in the air and the town is on the edge: Napoleon’s rise to power has France’s neighbours on high alert, and unprecedented industrial change is making the lives of ordinary workers a misery. We met with Ken Follett at Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire, where he researched the cloth mills in which the characters from The Armour of Light work.

You’ve written thirty-seven books, which have been sold in over eighty countries and translated into forty languages. Which has been your favourite to write and why?

Eye of the Needle, because it was so easy and that's never happened to me again. It happens to creative people occasionally – it all just seems to keep flowing out, like Paul McCartney writing Yesterday by George Harrison’s swimming pool while he was waiting for George to get dressed. And I just wrote this one very quickly. I had three weeks off work and I wrote most of it in those three weeks. I look at it and I think: did I write that when I was 27?!

And what was the most challenging book to write?

The Pillars of the Earth. I had never written that kind of book before, and never written a book that long. The real challenge was to tell the story of how a cathedral is built without getting bogged down in technicalities – and the technicalities of cathedral building are pretty complicated! I had a famous book called The Construction of Gothic Cathedrals and I had to try to take from that the essence, the bones of it, and make it clear and easily comprehensible to the reader. It was also difficult for me to write 375,000 words because previously all my books have been around 90 to 100,000 words. And the thing about a long book is you’ve got to keep on making up more stuff about the same group of characters!

Many of your novels explore historical moments when individual people could change the course of history forever. What do you think are some of the most fascinating examples of that happening?

I think famous individuals in history ride a wave – I don't think they do it on their own – so you have to look for somebody whose individual talents made a real difference. I think you've got to count Napoleon as one of those, because he was such a great general he won battles which he ought to have lost. Another interesting person in this regard is Clement Attlee, Labour MP and Prime Minister after the war. The men coming back from war were very down to earth and everybody had seen how social action helped us win, and were open to things like the National Health Service. And Attlee rode that wave and made a big difference to British society. Perhaps also Queen Elizabeth I. She was a great leader, a great figurehead, at a time when England was under attack from Spain, which was the richest and most powerful country in the world at that time. They are all people who rode a wave but also had exceptional talents.

Of all the books you have read, which do you think have shaped you the most?

When I was twelve years old I read Live and Let Die by Ian Fleming, and I reread it, actually for the third time, quite recently. It's terrific. I became a James Bond fan, and when I started to write novels myself I remembered the thrill of being twelve and having a new James Bond novel in my hands to read. And I thought: that's what I need my readers to feel. I really wanted people to say ‘oh great, it's a new Ken Follett.’ And that's a high bar. So I set myself a high ambition: that was the way that Ian Fleming influenced me. I don't write like him. You can’t write like him: he's got a very particular and quite brilliant prose style. But what remained was that feeling.

‘I remembered the thrill of being twelve and having a new James Bond novel in my hands to read. And I thought: that's what I need my readers to feel. I really wanted people to say ‘oh great, it's a new Ken Follett.’’

My model for how a long book should be structured is Orley Farm by Anthony Trollope. It's a courtroom drama, and it's a very long book. We don't actually get to the courtroom until about seven-eighths of the way through. There's a circle of characters and every time there's a development in the story, he goes around the circle showing how the development affects each character, and it's just perfection. When I started to write long novels with The Pillars of the Earth I thought, that’s how you can have a big cast: you've always got to include them all and the best way to do that is in a logical, structured way. You can’t write a long novel with multiple characters and just play it by ear. It’s got to be structured, and Trollope’s plan for Orley Farm was a perfect example of a plan for a long novel.

In previous interviews you’ve said that you were actually quite bored by history at school. What changed?

I started out writing spy stories. And I decided that the spy story would be more thrilling if the activities of the spy affected some real event in history: the course of a battle or the course of a war. So first of all I wrote Eye of the Needle, which was a spy story leading up to D-Day. And then I started to read military history to find examples of battles and wars where the spy’s action made a difference or might have made a difference. So I got into military history that way. And then my horizons expanded and instead of just writing thrillers I began to write general historical novels – but still looking at real history to find those gems where true history gives you a set of characters whose lives are exciting.

When did you know you first wanted to be a writer?

My first job was as a newspaper reporter and while I was doing that I realised that I didn't really love newspapers! But I did love novels, and I started to think then about trying to write one. I wrote quite a lot of books in my spare time when I was working as a journalist and then later when I moved and worked for a publisher. Although they were published they were not very successful. So I did ten books that didn't make any waves at all, but I knew I was getting better and then it all came together with Eye of the Needle.

‘If I was bored, I’d write something boring and then the readers would be bored. I think it is very, very hazardous to do the same thing again and again.’

You're no stranger to genre hopping. What's the appeal for you in writing in different genres?

I've always felt that if I can think of a good story it doesn't matter too much what the genre is, because I'll be thrilled with it and I'll be able to communicate the excitement to the reader, so I think that's the appeal. It's also very important for a writer not to get bored. If I was bored, I’d write something boring and then the readers would be bored. I think it is very, very hazardous to do the same thing again and again. And it wouldn't suit me.

How do you do your research?

I start with books. Maps. Photographs, or paintings if the story is set in the time before photography was invented. Film later on. If it's something within living memory then I can interview people who’ve lived through it. For example, Night Over Water is about a seaplane that was built before the Second World War and I was able to track down people who had been crew on the plane and ask them about the experience. Or I might interview an expert in a particular field. For The Armour of Light I had the benefit of a military friend for whom Waterloo is a hobby and he and I went together to the Battlefield of Waterloo. Visiting places is really important. Coming to this place [Quarry Bank Mill] and seeing these machines really enabled me to give a vivid account of them in the book. And sometimes you realise that you’ve had a misconception about certain things from the books that you've read and so it can be corrective. It always starts with the books and towards the end of the process the visit gives me that gloss; it gives me that ability to make the description vivid.

Your Kingsbridge novels span nearly a thousand years but are all set in the same fictional city. What made you set them in that one location and pick different points in time?

It happened gradually. A World Without End I conceived as a sequel to The Pillars of the Earth. Then I discovered that Queen Elizabeth I founded the first English Secret Service and I thought, now that sounds like a Ken Follett story! And then I thought, why not set it at least partly in Kingsbridge? And that became a thing. I quite enjoy going back to Kingsbridge, and readers like it. It's also become sort of a badge for a certain type of story by me.

The Armour of Light

by Ken Follett

In 1792, England hungers for supremacy while France witnesses Napoleon's ascent. Meanwhile, Kingsbridge, a once-tranquil town, stands on the brink. Industrial innovation sweeps the land, shattering the lives of workers and tearing families apart. In the face of encroaching tyranny, a small but resolute group from Kingsbridge emerges. Their intertwined stories encapsulate a generation's struggle for enlightenment, as they rally against oppression and fight passionately for a future free from the shackles of an oppressive regime. The Armour of Light is the latest instalment in Ken Follett's Kingsbridge series.

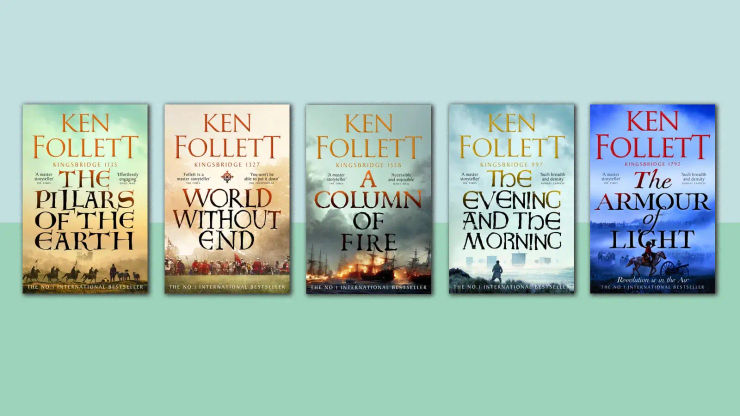

The Kingsbridge novels

Author photo: Olivier Favre