Fiction

Lucinda Riley's The Seven Sisters books in order

The best fiction books of 2026, and all time

Elevator pitch reads: five books with irresistible hooks

40 of the best romance novels of all time

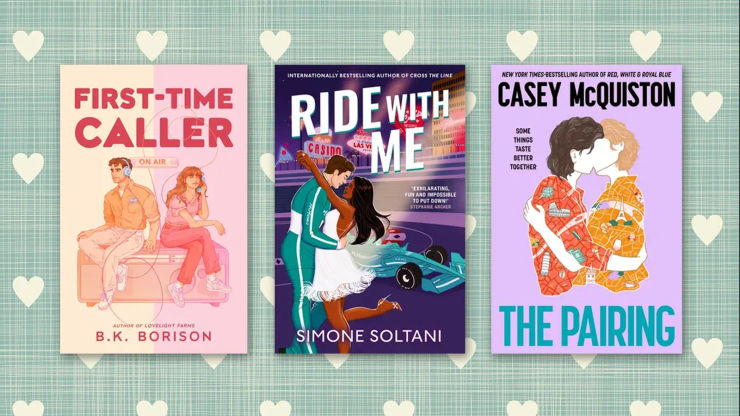

The best rom com books to read right now

A guide to romance writer BK Borison's books

Kristin Hannah’s books: a complete guide

Must-read Sapphic romance books and love stories

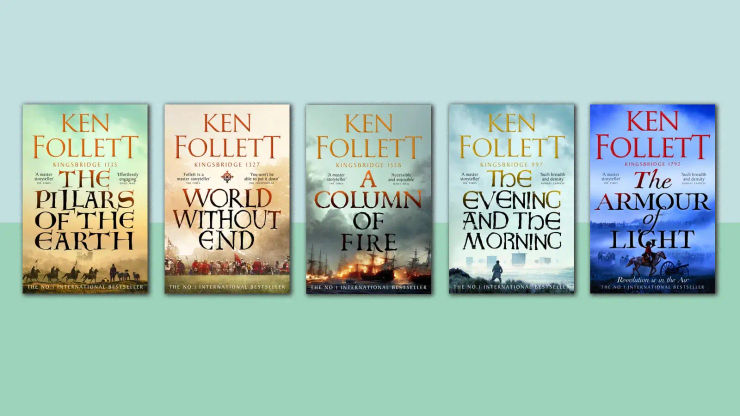

Ken Follett's Kingsbridge books in order

Books to read if you love Emily Henry

Danielle Steel: a guide to her latest books & bestsellers

Brilliant books based on folklore